It is volume 45 (44 43 42 41 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0)

This is a part of a raw and uneven journal of discovering the origins of the writing systems,

so I recommend you to read the summary of this

work instead.

God jul [гу юль] is Merry Christmas in

Norwegian. Cool lads, they preserved the old name of

the holiday. Yule. Unless it's Y the cross and ju the

jew. But then I have no right to say so, God is good

[гу]

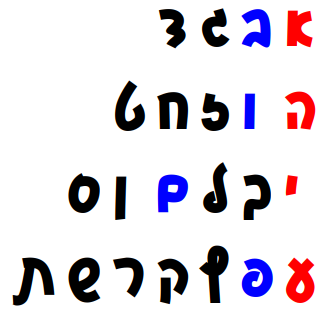

רַע [ra] is bad and evil in hebrew (which is perfectly in line with god/гад and such)

But then ע is at the Ѹ position, so it' Ro or Ru. As ro it's cognate to wrong. Is w in wrong the same as in jew? is je the? W (wars, swarы, wrong in general, wgly, but I'm being antisemitic, that's not cool)

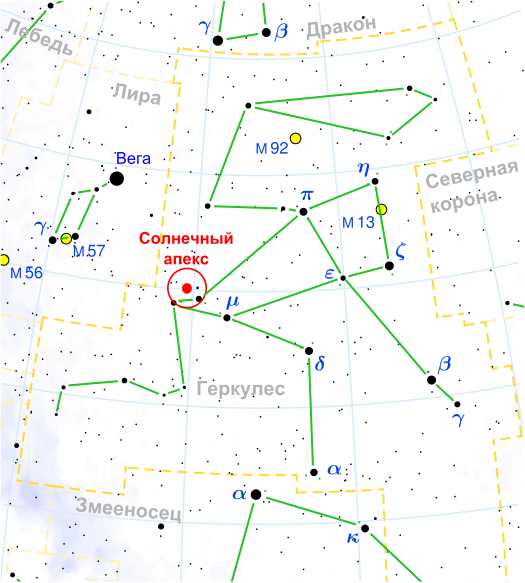

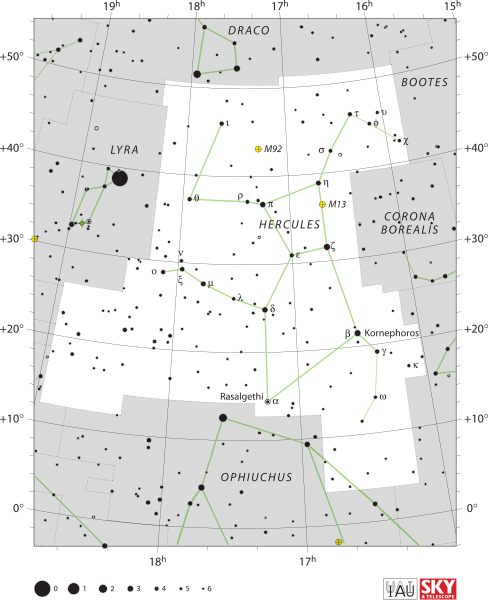

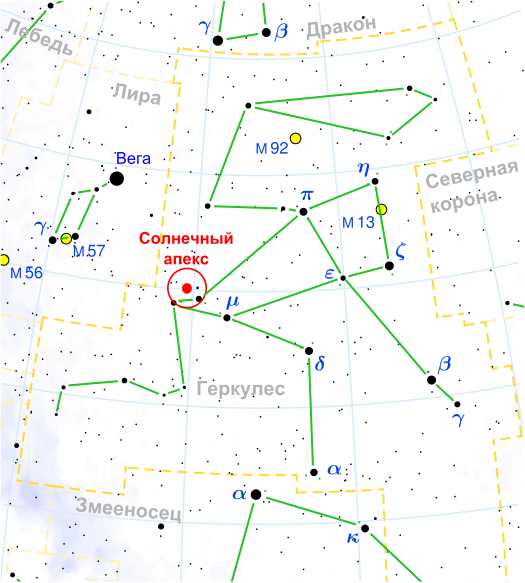

w in wrong is the same as in war. war is wrong, wrong is warring. strong is starring. long is alling? всё (продолжается и продолжается, being on and on, but that's I'm trying too hard. strong guys are stars it's natural, Hercules is in the sky, is he not, and we hardly know what the other constellations are famous for, so ancient are those gods. Bears? Ursa. Ur's? ᛒᚱ ᚢᚱ ᚱᚢ belarus ural rus? ᛒᚱ ᚱᚢ ᚢᚱ)

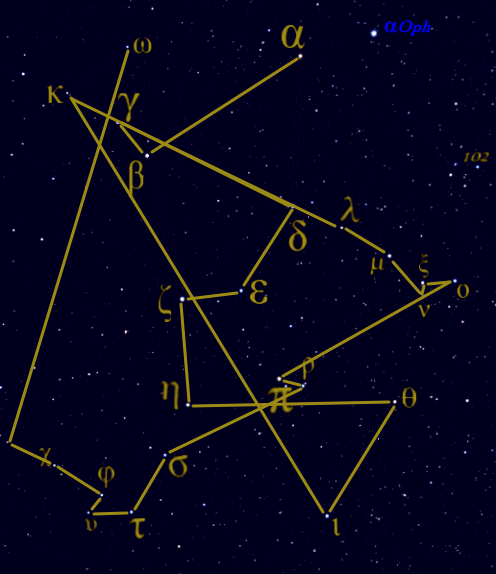

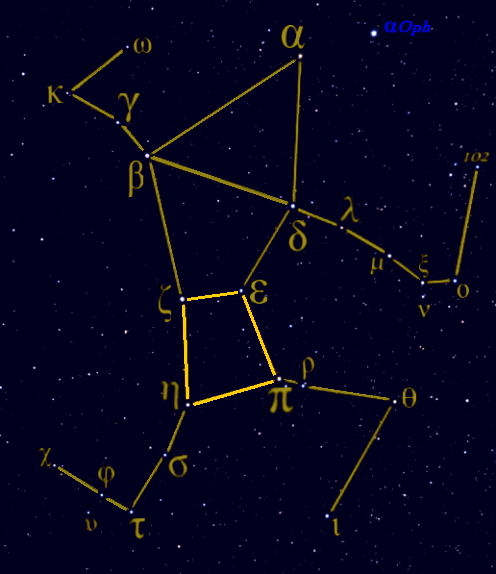

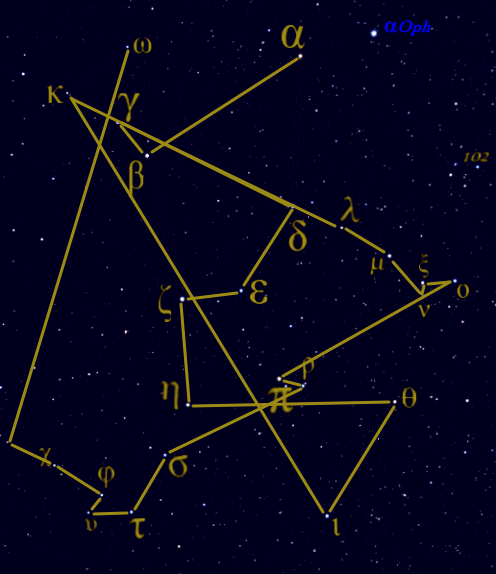

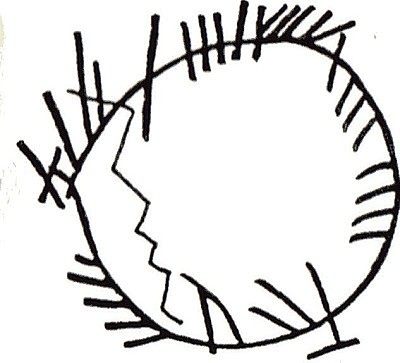

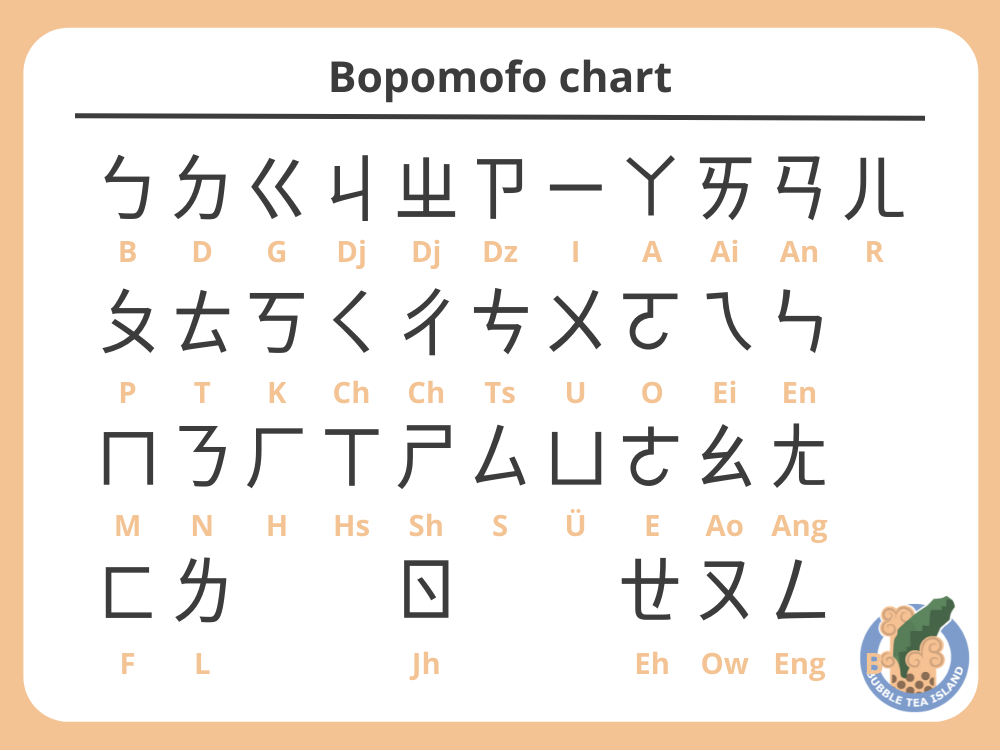

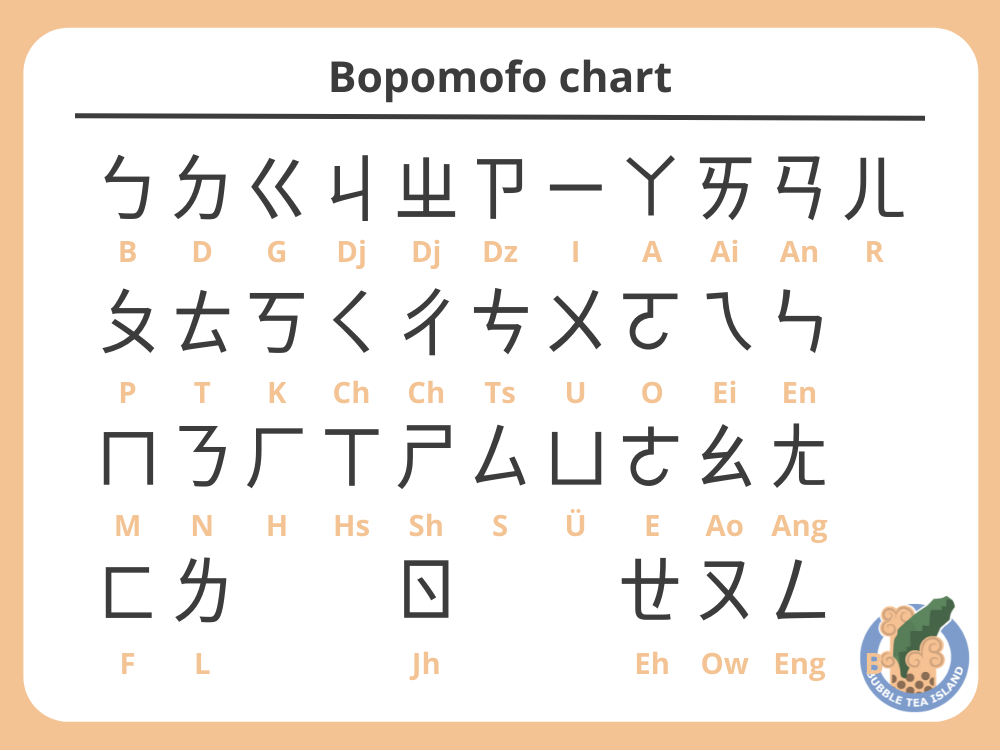

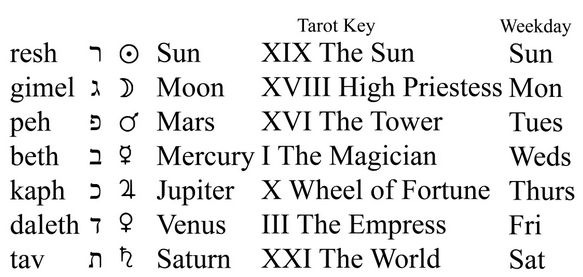

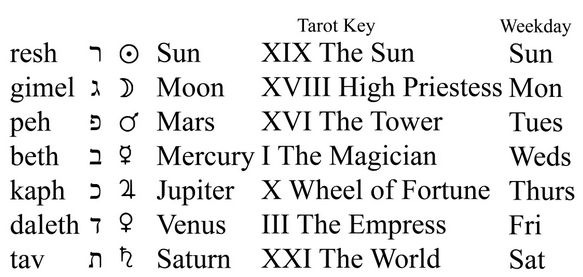

This depiction is simply the best, but just as with the zodiac, it has other readings (and it reminds me of how letters look differently in different cultures)

And they say best or not best, it's a recent development: An alternative way to connect the stars of the constellation Hercules, suggested by H.A. Rey. Here, Hercules is shown with his head at the top.

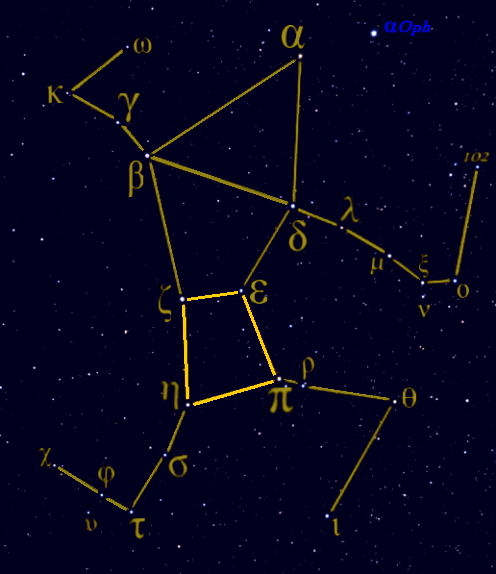

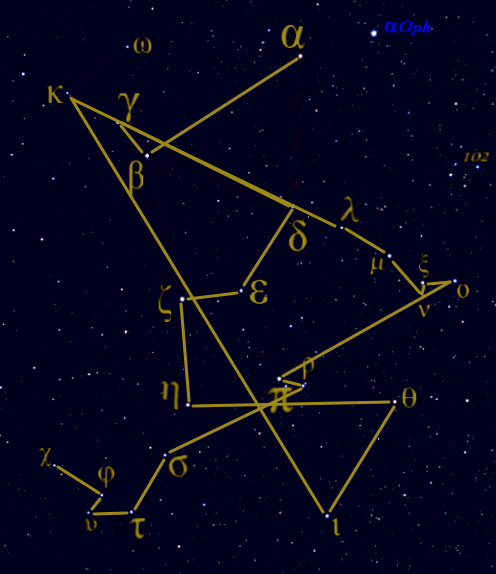

and here's something more traditional, as they say:

and another one, similar to this one with the Keystone asterism:

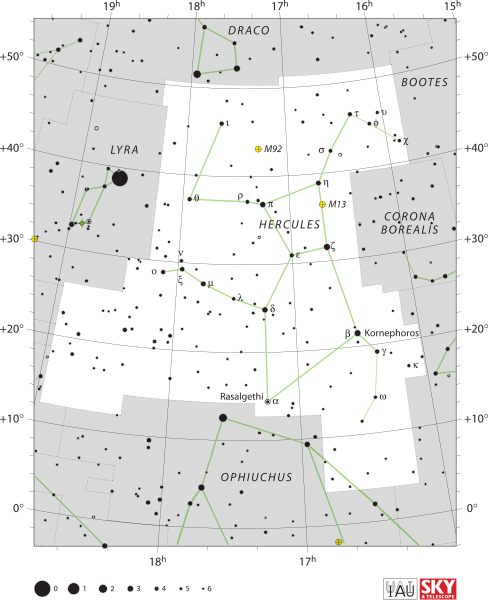

And here's where I took that Keystone asterism: (I should learn the asterism, they could be something)

Traditional view of the Hercules constellation highlighting the quadrangle which forms the Keystone asterism:

It contains as many stars as there are letters in the greek alphabet, only I do not see ψ,

which makes me wonder if that 102 is ψ, which would make sense since ω is another hand.

And what awes me is how I just spoke about hands being the final development of the human body.

Just in the previous volume few days ago, if not yesterday, in completely different context.

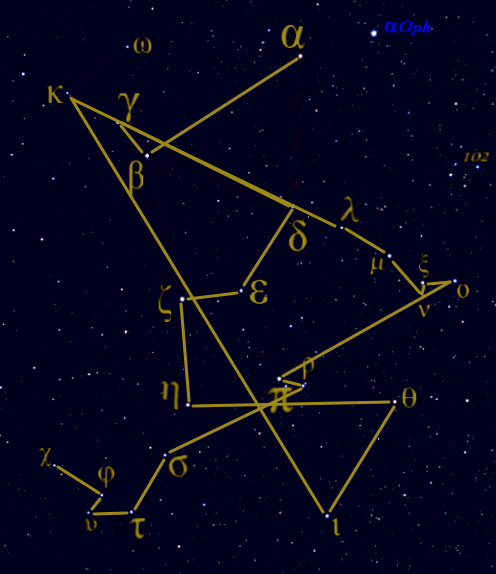

So, let's connect those stars alphabetically, see what we get.

and here I stopped, because ψ is missing, and connecting χ to the star 102 made no sense,

because here I can see a face with open mouth, in a helmet, with στυφχ being the neck,

or is it a coincidence of δ (not the star but the letter) being such a good eye?

ρ as tongue makes so much sense with "речь" (but in greek tongue is γλώσσα,

and speech is ομιλία, λόγος, φωνή, λαλιά)

(in norwegian speech is supercool: tale (tale is eventyr))

So I went to look for the ψ:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_of_stars_with_Bayer_designations

and it tells that ψ Her is Also designated as Nu2 Boötis (ν2 Boo)

What it tells is that the constellation Boots has not one, but two ν's,

and the second one used to be ψ of the Heracules.

Ptolemy considered Nu2 Boötis to be shared by Hercules, and Bayer assigned it a designation in both constellations: Nu2 Boötis (ν2 Boo) and Psi2 Herculis (ψ2 Her). When the modern constellation boundaries were fixed in 1930, the latter designation dropped from use.[13]

and this ψHer frames the head perfectly. With the ends of the polygram being the α and ω above teh crown, and I wonder if they're the arrows in the helmet,

But then such face is rather cartoonish, but then who said they used straight lines for that..

well, what else would they use?

Well, let's consider it my representation of Hercules. The depiction of his helmet,

but then this helmet looks too medieval, greek helmets don't seem to have used the moving parts.

μ and ν being around the nose area are extremely nice.

But then is ξ legit? Latin alphabet doesn't have it (oh, I have to check if there was some roman numeration. That table of stars with Bayer designation includes the latin stars, but what they are I didn't look into them yet to tell. If ξ was added later, ν could be what they call ξ now, but that's a bold and naked speculation, but then it is a ground to check some day, who knows, maybe I've got that intuition already)

γδ going for forehead and sharing the same line with κλ going for helmet is super awesome too.

It's fascinating how strong ~ starring coming from wrong ~ warring lead me to this.

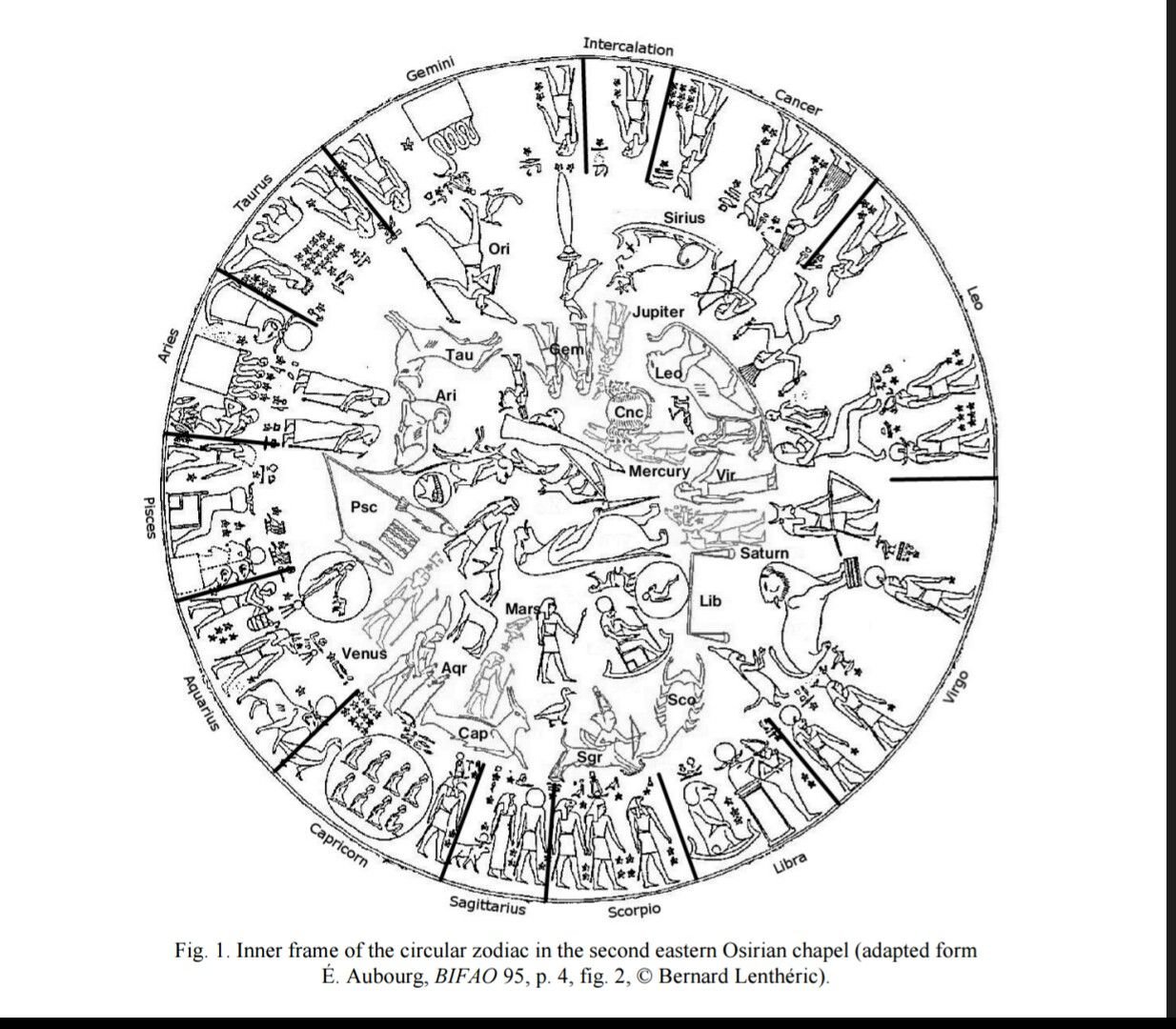

Hercules was one of the 48 constellations listed by the second-century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations today. It is the fifth-largest of the modern constellations and is the largest of the 50 which have no stars brighter than apparent magnitude +2.5.

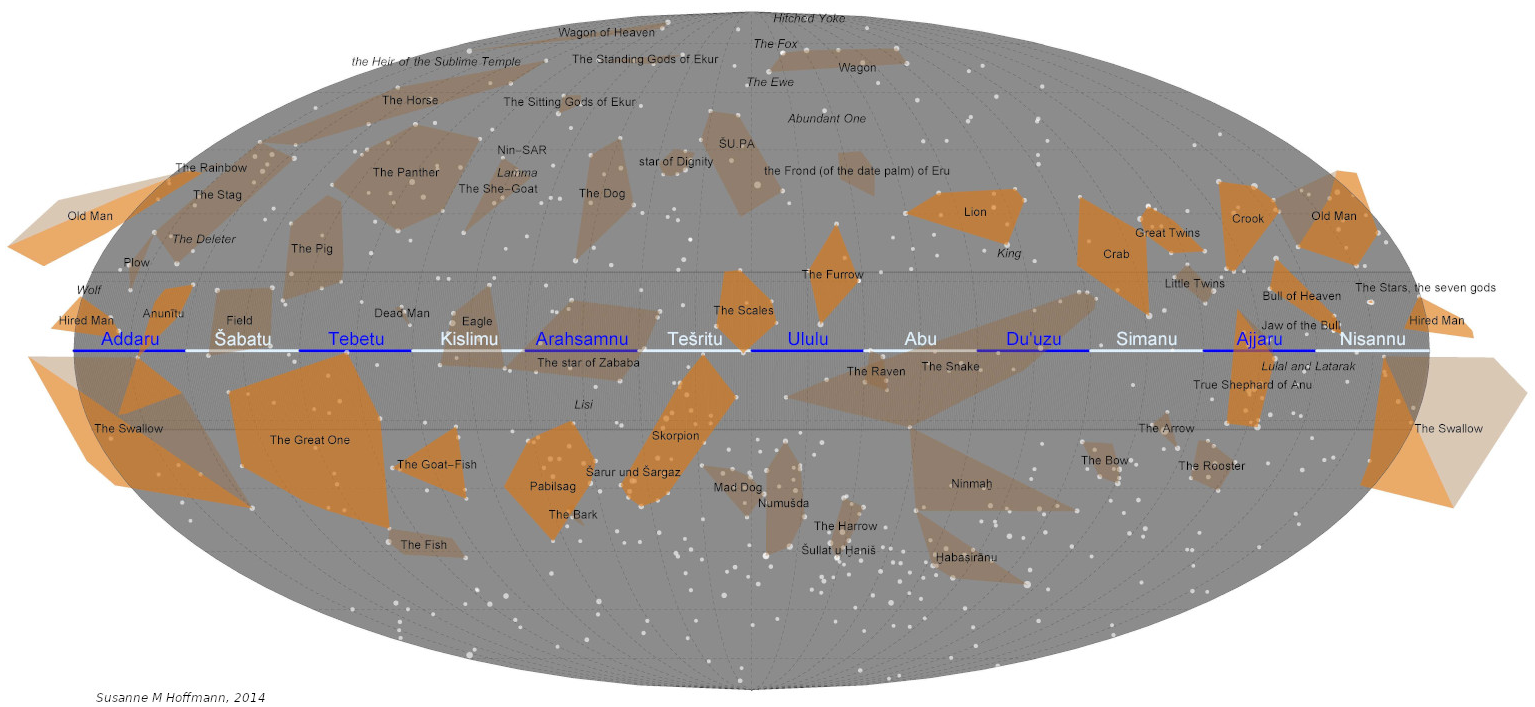

According to Gavin White, the Greek constellation of Hercules is a distorted version of the Babylonian constellation known as the "Standing Gods" (MUL.DINGIR.GUB.BA.MESH). White argues that this figure was, like the similarly named "Sitting Gods", depicted as a man with a serpent's body instead of legs (the serpent element now being represented on the Greek star map by the figure of Draco that Hercules crushes beneath his feet). He further argues that the original name of Hercules – the 'Kneeler' (see below) – is a conflation of the two Babylonian constellations of the Sitting and Standing Gods.[34]

The constellation is also sometimes associated with Gilgamesh, a Sumerian mythological hero.[10] Phoenician tradition is said to have associated this constellation with their sun god, who slew a dragon (Draco).[35]

The earliest Greek references to the constellation do not refer to it as Hercules. Aratus describes it as follows:

Right there in its [Draco's] orbit wheels a Phantom form, like to a man that strives at a task. That sign no man knows how to read clearly, nor what task he is bent, but men simply call him On His Knees. [Ἐγγόνασιν "the Kneeler"].[36]

Now that Phantom, that toils on his knees, seems to sit on bended knee, and from both his shoulders his hands are upraised and stretch, one this way, one that, a fathom's length. Over the middle of the head of the crooked Dragon, he has the tip of his right foot. Here too that Crown [Corona], which glorious Dionysus set to be memorial of the dead Ariadne, wheels beneath the back of the toil-spent Phantom. To the Phantom's back the Crown is near, but by his head mark near at hand the head of Ophiuchus [...] Yonder, too, is the tiny Tortoise, which, while still beside his cradle, Hermes pierced for strings and bade it be called the Lyre [Lyra]: and he brought it into heaven and set it in front of the unknown Phantom. That Croucher on his Knees comes near the Lyre with his left knee, but the top of the Bird's head wheels on the other side, and between the Bird's head and the Phantom's knee is enstarred the Lyre.[37]

The constellation is connected with Hercules in De astronomia (probably 1st century BCE/CE, and attributed to Hyginus), which describes several different myths about the constellation:

Eratosthenes (3rd century BCE) is said to have described it as Hercules, placed above Draco (representing the dragon of the Hesperides) and preparing to fight it, holding his lion's skin in his left hand, and a club in his right (this can be found in the Epitome Catasterismorum[38]).

Panyassis' Heracleia (5th century BCE) reportedly said Jupiter was impressed by this fight, and made it a constellation, with Hercules kneeling on his right knee, and trying to crush Draco's head with his left foot, while striking with his right hand and holding the lion skin in his left.

Araethus (3rd/4th century BCE) is said to have described the constellation as depicting Ceteus son of Lycaon, imploring the gods to restore his daughter Megisto who had been transformed into a bear.

Hegesianax (2nd/3rd century BCE), who it says describes it as Theseus lifting the stone at Troezen.

Anacreon of Alexandria, who it claims also supports the idea that it depicts Theseus, saying that the constellation Lyra (said to be Theseus' lyre in other sources) is near Theseus.

Thamyris blinded by the Muses, kneeling in supplication.

Orpheus killed by the women of Thracia for seeing the sacred rituals of Liber (Dionysus).

Aeschylus' lost play Prometheus Unbound (5th century BCE), which recounted that when Hercules drives the cattle of Geryon through Liguria (northern Italy), the Ligurians will join forces and attack him, attempting to steal the cattle. Hercules fights until his weapons break, before falling to his knees, wounded. Jupiter, taking pity on his son, provides many stones on the ground, which Hercules uses to fight off the Ligurians. In commemoration of this, Jupiter makes a constellation depicting Hercules in his fighting form. (A quote from this section of the play is preserved in Dionysius of Halicarnassus' Roman Antiquities: "And thou shalt come to Liguria's dauntless host, Where no fault shalt thou find, bold though thou art, With the fray: 'tis fated thy missiles all shall fail."[39])

Ixion with his arms bound for trying to attack Juno.

Prometheus bound on Mount Caucasus.[40]

The Scholia to Aratus mention three more mythical figures in connection with this constellation: Sisyphus or Tantalus, who suffered in Tartarus for having offended the gods, or Salmoneus, who was struck down by Zeus for his hubris.[38] Another classical author associated the constellation with Atlas.[35]

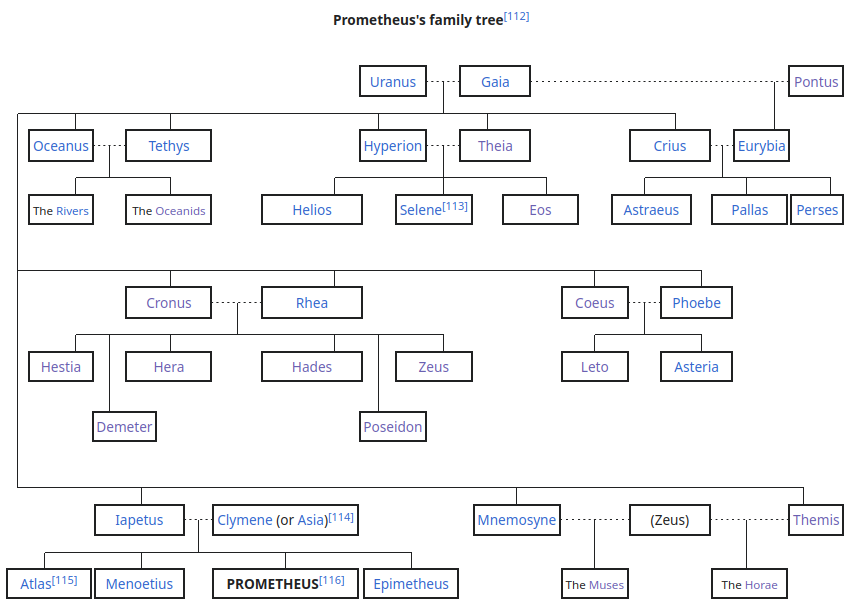

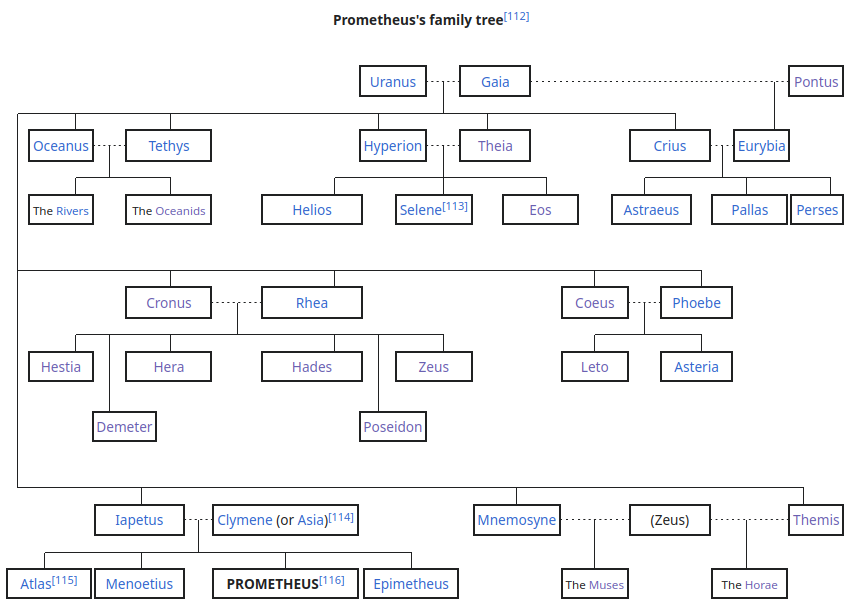

And I wonder if I read this table correctly, and yes, those are all children of Gaia:

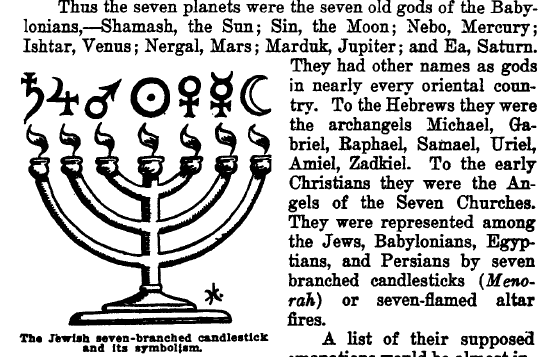

Gaia and Ouranos together had twelve children first which were called the twelve Titans. They consisted of six males - Oceanus, Hyperion, Coeus, Cronus, Crius, and Iapetus and six females - Mnemosyne, Tethys, Theia, Phoebe, Rhea, and Themis.

Notice, how male and female deities have different initial letters in names, how labial initials belong to females, it's something I have to revisit some other time.

So far it definitely raises the question of Rh being labial (the weird question I raise again and again)

And the other one could have the second syllable being the root of the name:

In Greek mythology, Tethys (/ˈtiːθɪs, ˈtɛ-/; Ancient Greek: Τηθύς, romanized: Tēthýs) was a Titan daughter of Uranus and Gaia, a sister and wife of the Titan Oceanus, and the mother of the river gods and the Oceanids. Although Tethys had no active role in Greek mythology and no established cults,[2] she was depicted in mosaics decorating baths, pools, and triclinia in the Greek East, particularly in Antioch and its suburbs, either alone or with Oceanus.

I know it's a shameless pull, but then θ of θεά, and of two of her sisters. And one of them is literally θεά

Theia (/ˈθiːə/; Ancient Greek: Θεία, romanized: Theía, lit. 'divine', also rendered Thea or Thia), also called Euryphaessa (Ancient Greek: Εὐρυφάεσσα, "wide-shining"), is one of the twelve Titans, the children of the earth goddess Gaia and the sky god Uranus in Greek mythology. She is the Greek goddess of sight and vision, and by extension the goddess who endowed gold, silver, and gems with their brilliance and intrinsic value.[2]

Her brother-consort is Hyperion, a Titan and god of the sun, and together they are the parents of Helios (the Sun), Selene (the Moon), and Eos (the Dawn). She seems to be the same figure as Aethra, who is the consort of Hyperion and mother of his children in some accounts.[3] Like her husband, Theia features scarcely in myth, being mostly important for the children she bore, though she appears in some texts and rare traditions.

Norwegian word for goddess, gudinne, has the same root with the english root, and the same suffix with the russian word богиня.

И океан шумит. Тяжелым низким гулом, слышимым издалека... Не шум прибоя: периодически накатывающихся волн, но - ровный рокот.

что объясняет почему буква М связана с водой; а, как замечено выше, буква S — с лесом.

the sea (starts with S for some reason) is M because it raises up and down (but those who called it sea probably thought of ebb and flow (flux and reflux (flow is flux, both are прилив)))

Mare is the latin word for sea.

And if these agregate states of matter are M and S, it is only natural to consider A to be the 3ʳᵈ one, air.

But, I wonder what made jews turn earth in fire.. probably because it burns, and they're destroyers.

But language is yet to reveal that thought:

א can be both, אויר and אֶרֶץ ..and אֵשׁ

and אש

(g.t. reads them эш and аш, but who knows, and what does it matter)

מַיִם is the only opoposi.. opposite to them.

and such opposition, אם

אמ

can be the difference of solid water and the other half of the world..

If water is solid, which the form of ם told me, then water and land are one.

But isn't that a deeper elaboration of the liquid-solid separation?

But in the world of mud who could separate the two? There are more and less watery matter, but even the most solid solid melts.

Meanwhile the separation of air and land is directly observable. Always was.

אם is ॐ

Didn't the flying diacritics of ॐ giving birth to the third element? Air it was? ॐ looks as if it's om read in “ॐ अम ओम्

Om (or Aum) (listenⓘ; Sanskrit: ॐ, ओम्, romanized: Oṃ, Auṃ, ISO 15919: Ōṁ)

is a polysemous symbol representing a sacred sound, syllable, mantra, and invocation in Hinduism.[1][2]

Its written form is the most important symbol in the Hindu religion.[3]

It is the essence of the supreme Absolute,[2] consciousness,[4][5][6] Ātman, Brahman, or the cosmic world.[7][8][9]

In Indic traditions, Om serves as a sonic representation of the divine,

a standard of Vedic authority and a central aspect of soteriological doctrines and practices.[10]

It is the basic tool for meditation in the yogic path to liberation.[11]

The syllable is often found at the beginning and the end of chapters in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts.[9]

It is described as the goal of all the Vedas. [12]

Atman and Brahman are A and B, and probably those very ओ and म्

самый открытый звук и самый закрытый

такое закрытое B, что не разрывается

(но иногда эту мантру поют по кругу, тогда м продолжается сколько хватает воздуху, чтоб продолжиться вдохом и повторением)

Тогда это рот и нос!

Петь имеет смысл чтоб поровну разделить энергию меж ними

(у меня получи лось пять пальцев на правой открыть пока пел А

и затем пять пальцев на елв елевой открыть пока пер пел М)

Nose Mose? Moses ~ Noses!!!

The syllable Om is referred to by many

names, including:

Praṇava (प्रणव); literally, "fore-sound", referring to Om as the primeval sound.[21][22]

Oṅkāra (ओङ्कार) or oṃkāra (ओंकार);

Udgītha (उद्गीथ); meaning "song, chant", a word found in Samaveda and bhasya (commentaries) based on it.

Ekākṣara; literally, "one letter of the alphabet", referring to its representation as a single ligature.

The etymological origins of ōm (aum) have long been discussed and disputed, with even the Upanishads having proposed multiple Sanskrit etymologies for aum, including: from "ām" (आम्; "yes"), from "ávam" (आवम्; "that, thus, yes"), and from the Sanskrit roots "āv-" (अव्; "to urge") or "āp-" (आप्; "to attain").[28][A] In 1889, Maurice Bloomfield proposed an origin from a Proto-Indo-European introductory particle "*au" with a function similar to the Sanskrit particle "atha" (अथ).[28] However, contemporary Indologist Asko Parpola proposes a borrowing from Dravidian "*ām" meaning "'it is so', 'let it be so', 'yes'", a contraction of "*ākum", cognate with modern Tamil "ām" (ஆம்) meaning "yes".[28][29] In the Jaffna Tamil dialect spoken in Sri Lanka, aum' is the word for yes.

The syllable Om is first mentioned in the Upanishads. It has been associated with various concepts, such as "cosmic sound", "mystical syllable", "affirmation to something divine"

And at that sentenced I first found it in amen, and then I recalled that Essens tell aumen instead of amen (a hear-say, didn't check it yet) and thus am in amen is literally aum, am as yes.

, or as symbolism for abstract spiritual concepts in the Upanishads.[9] In the Aranyaka and the Brahmana layers of Vedic texts, the syllable is so widespread and linked to knowledge, that it stands for the "whole of Veda".[9] The symbolic foundations of Om are repeatedly discussed in the oldest layers of the early Upanishads.[32][33] The Aitareya Brahmana of Rig Veda, in section 5.32, suggests that the three phonetic components of Om (a + u + m) correspond to the three stages of cosmic creation, and when it is read or said, it celebrates the creative powers of the universe.[9][34]

That sentence made me recall that אמת on golems' forehead begins with that אמ.

However, in the eight anuvaka of the Taittiriya Upanishad, which consensus research indicates was formulated around the same time or preceding Aitareya Brahmana, the sound Aum is attributed to reflecting the inner part of the word Brahman. Put another way, it is the Brahman, in the form of a word.[35] The Brahmana layer of Vedic texts equates Om with bhur-bhuvah-svah, which symbolizes "the whole Veda". They offer various shades of meaning to Om, such as it being "the universe beyond the sun", or that which is "mysterious and inexhaustible", or "the infinite language, the infinite knowledge", or "essence of breath, life, everything that exists", or that "with which one is liberated".[9] The Samaveda, the poetical Veda, orthographically maps Om to the audible, the musical truths in its numerous variations (Oum, Aum, Ovā Ovā Ovā Um, etc.) and then attempts to extract musical meters from it.[9]

bhur-bhuvah-svah is an interesting utterance, because bhur-bhuvah starts the same, so is probably the same just with different suffixes, and svah opposes bhuvah as S and Bhu, as S and M basically.

faculty ~ vacuity

race ~ rage (what rage are you (for in more common sense, ragi is a vehement desire or passion:

I hate word fix, so narrow. A stick between wheels may fix them, but as russian I see зафиксировать in fix first and foremost.

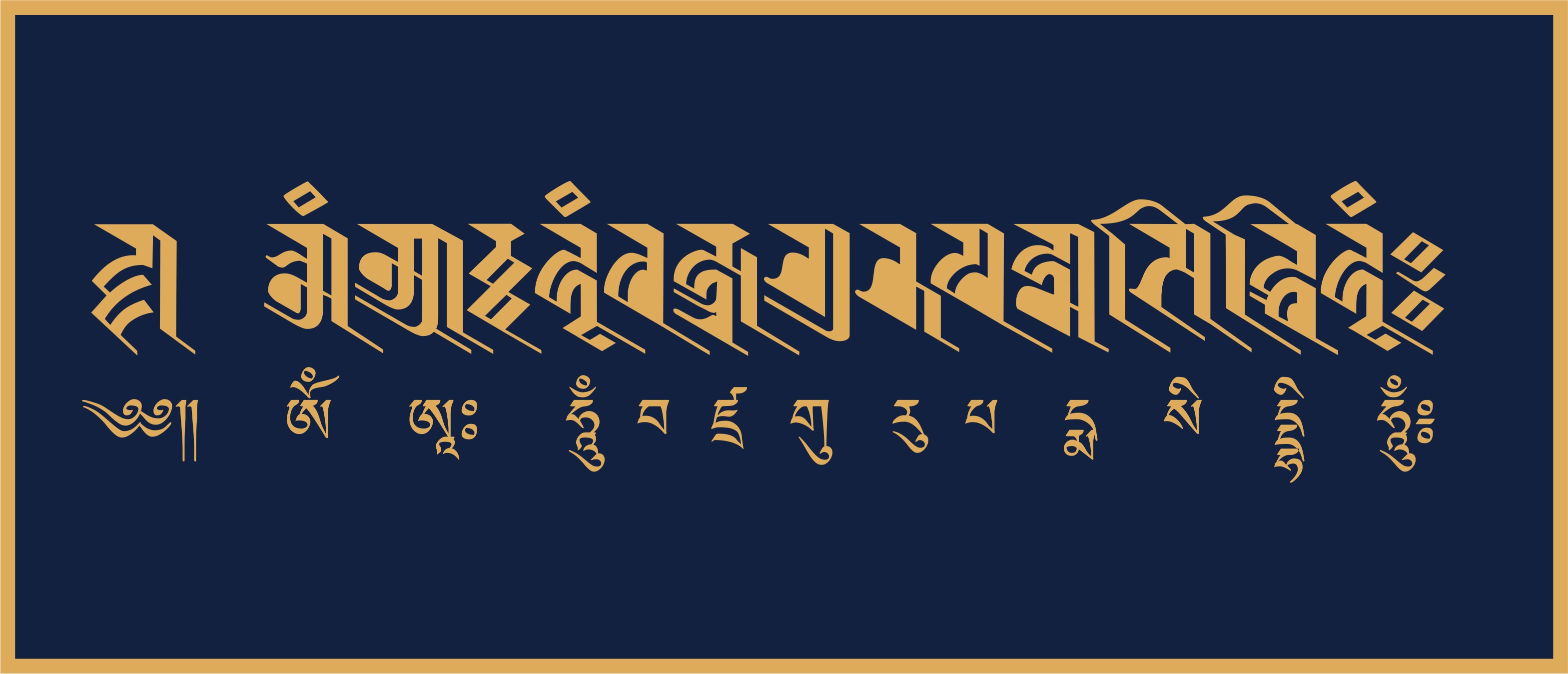

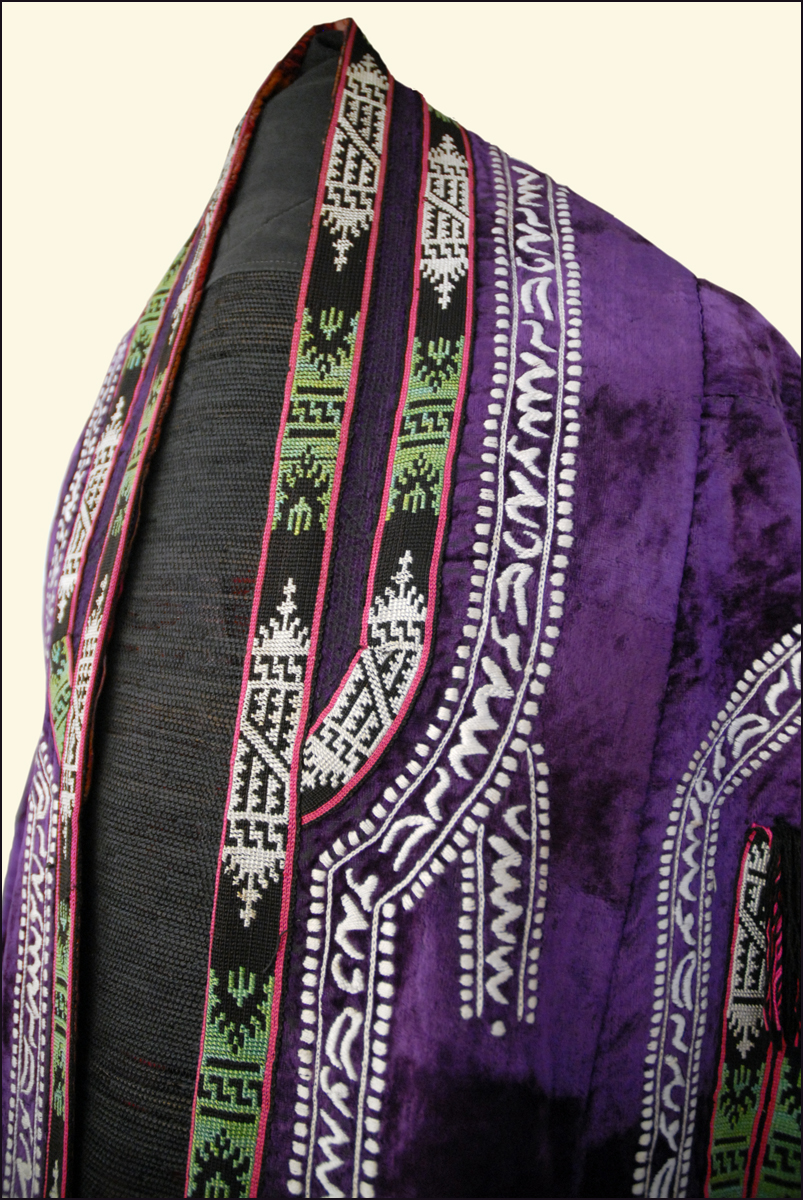

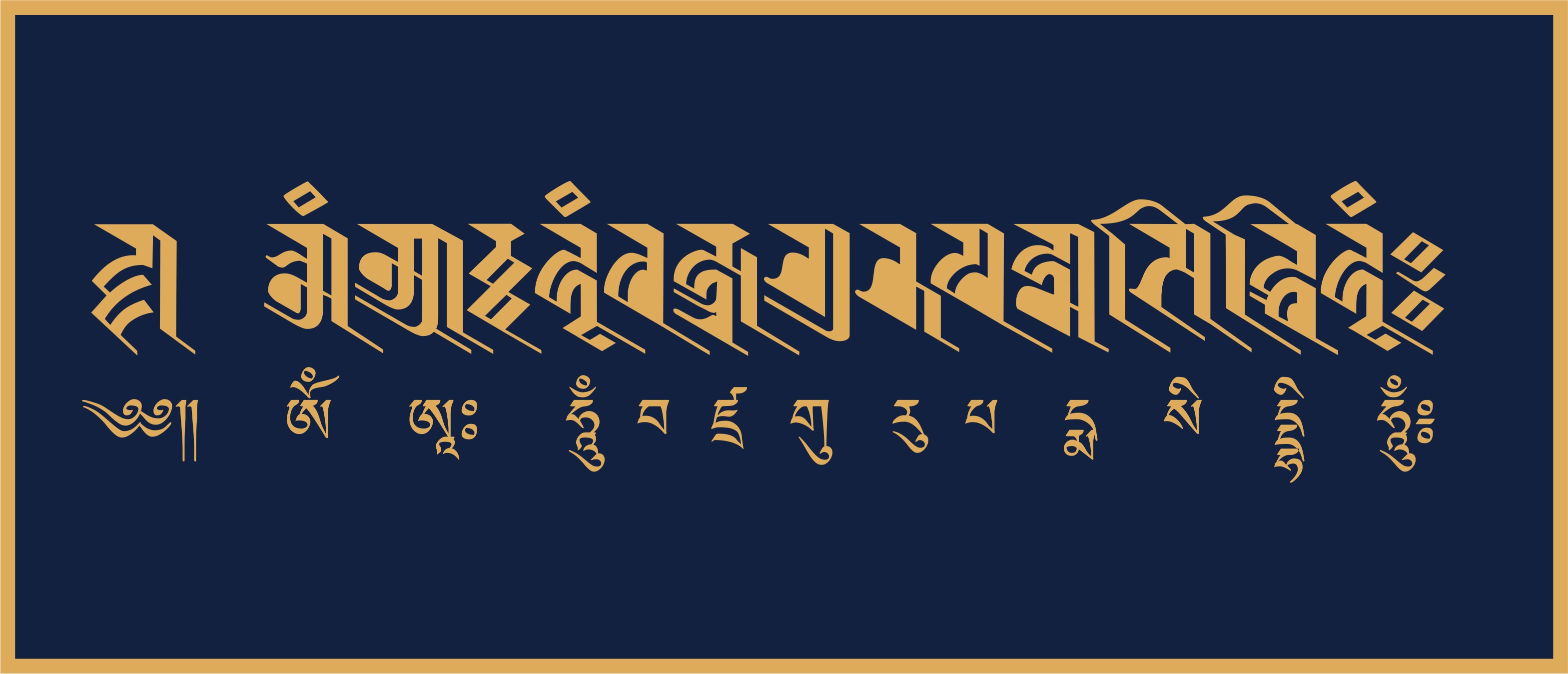

My friend wished that I research eastern cultures more, and his wish is granted:

(not by my will, I just observe working into this thing, being fascinated by shapes of Pali)

In the oldest texts of Buddhism, dhyāna (Sanskrit: ध्यान) or jhāna (Pali: 𑀛𑀸𑀦) is a component of the training of the mind (bhavana), commonly translated as meditation, to withdraw the mind from the automatic responses to sense-impressions and "burn up" the defilements, leading to a "state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi)."[1] Dhyāna may have been the core practice of pre-sectarian Buddhism, in combination with several related practices which together lead to perfected mindfulness and detachment.[2][3][4]

In the later commentarial tradition, which has survived in present-day Theravāda, dhyāna is equated with "concentration", a state of one-pointed absorption in which there is a diminished awareness of the surroundings. In the contemporary Theravāda-based Vipassana movement, this absorbed state of mind is regarded as unnecessary and even non-beneficial for the first stage of awakening, which has to be reached by mindfulness of the body and vipassanā (insight into impermanence). Since the 1980s, scholars and practitioners have started to question these positions, arguing for a more comprehensive and integrated understanding and approach, based on the oldest descriptions of dhyāna in the suttas.[5][6][7][8]

In Buddhist traditions of Chán and Zen (the names of which are, respectively, the Chinese and Japanese pronunciations of dhyāna), as in Theravada and Tiantai, anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing), which is transmitted in the Buddhist tradition as a means to develop dhyana, is a central practice. In the Chan/Zen-tradition this practice is ultimately based on Sarvastivāda meditation techniques transmitted since the beginning of the Common Era.

Etymology

Dhyāna, Pali jhana, from Proto-Indo-European root *√dheie-, "to see, to look", "to show".[9][10] Developed into Sanskrit root √dhī and n. dhī,[10] which in the earliest layer of text of the Vedas refers to "imaginative vision" and associated with goddess Saraswati with powers of knowledge, wisdom and poetic eloquence.[11][12] This term developed into the variant √dhyā, "to contemplate, meditate, think",[13][10] from which dhyāna is derived.[11]

According to Buddhaghosa (5th century CE Theravāda exegete), the term jhāna (Skt. dhyāna) is derived from the verb jhayati, "to think or meditate", while the verb jhapeti, "to burn up", explicates its function, namely burning up opposing states, burning up or destroying "the mental defilements preventing [...] the development of serenity and insight."[14][note 1]

Commonly translated as meditation, and often equated with "concentration", though meditation may refer to a wider scale of exercises for bhāvanā, development. Dhyāna can also mean "attention, thought, reflection".[17]

Zoroastrianism in Persia, which has Indo-Aryan linguistic and cultural roots, developed the related practice of daena.

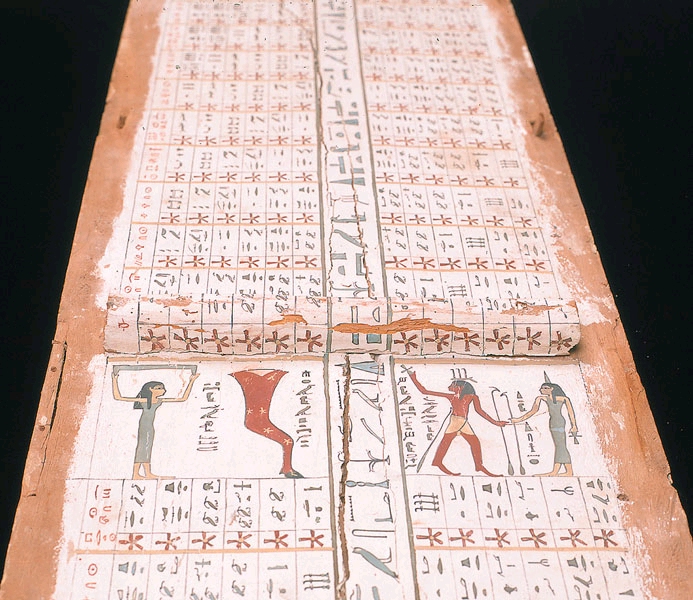

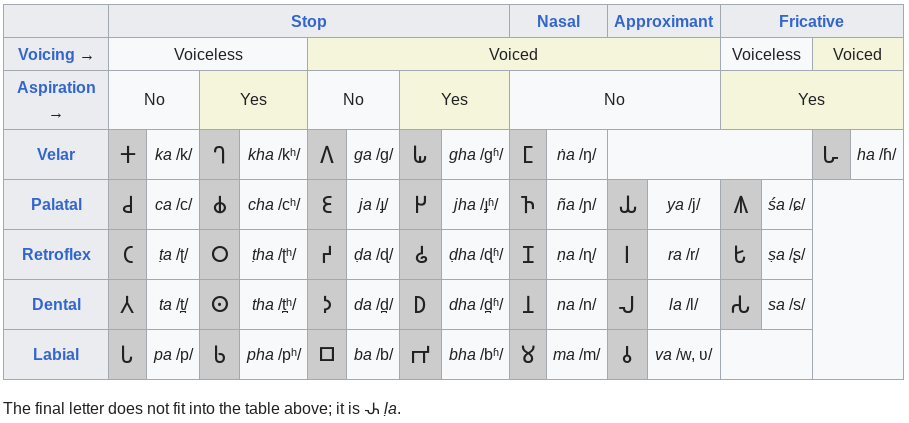

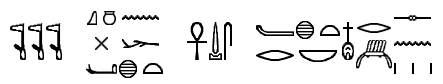

That Pali which fascinated me by its simple forms is in Brahmi script:

is it of агу?

רַע [ra] is bad and evil in hebrew (which is perfectly in line with god/гад and such)

But then ע is at the Ѹ position, so it' Ro or Ru. As ro it's cognate to wrong. Is w in wrong the same as in jew? is je the? W (wars, swarы, wrong in general, wgly, but I'm being antisemitic, that's not cool)

w in wrong is the same as in war. war is wrong, wrong is warring. strong is starring. long is alling? всё (продолжается и продолжается, being on and on, but that's I'm trying too hard. strong guys are stars it's natural, Hercules is in the sky, is he not, and we hardly know what the other constellations are famous for, so ancient are those gods. Bears? Ursa. Ur's? ᛒᚱ ᚢᚱ ᚱᚢ belarus ural rus? ᛒᚱ ᚱᚢ ᚢᚱ)

s syberia, t taiga (s~t)

япония на я,

последняя страна,

на краю океана

But looking at the map, even with some groups like lithuaina latvia haveing related names,

slovakia and slovenia, iraq and iran, kasakhstan-kyrgyztsan-kitay-korea similarities, no structure.

Anglia for A. Iceland as 1? Japan is not seen as the last letter by english. New Zealand was is!

It's a pareidolia, I suppose, but it may contribute how russians and englishmen see the world.

япония на я,

последняя страна,

на краю океана

But looking at the map, even with some groups like lithuaina latvia haveing related names,

slovakia and slovenia, iraq and iran, kasakhstan-kyrgyztsan-kitay-korea similarities, no structure.

Anglia for A. Iceland as 1? Japan is not seen as the last letter by english. New Zealand was is!

It's a pareidolia, I suppose, but it may contribute how russians and englishmen see the world.

This depiction is simply the best, but just as with the zodiac, it has other readings (and it reminds me of how letters look differently in different cultures)

And they say best or not best, it's a recent development: An alternative way to connect the stars of the constellation Hercules, suggested by H.A. Rey. Here, Hercules is shown with his head at the top.

and here's something more traditional, as they say:

and another one, similar to this one with the Keystone asterism:

And here's where I took that Keystone asterism: (I should learn the asterism, they could be something)

Traditional view of the Hercules constellation highlighting the quadrangle which forms the Keystone asterism:

α and ω, huh!

And I heard or read somewhere that Jesus is painted

from Hercules.It contains as many stars as there are letters in the greek alphabet, only I do not see ψ,

which makes me wonder if that 102 is ψ, which would make sense since ω is another hand.

And what awes me is how I just spoke about hands being the final development of the human body.

Just in the previous volume few days ago, if not yesterday, in completely different context.

So, let's connect those stars alphabetically, see what we get.

and here I stopped, because ψ is missing, and connecting χ to the star 102 made no sense,

because here I can see a face with open mouth, in a helmet, with στυφχ being the neck,

or is it a coincidence of δ (not the star but the letter) being such a good eye?

ρ as tongue makes so much sense with "речь" (but in greek tongue is γλώσσα,

and speech is ομιλία, λόγος, φωνή, λαλιά)

(in norwegian speech is supercool: tale (tale is eventyr))

So I went to look for the ψ:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_of_stars_with_Bayer_designations

and it tells that ψ Her is Also designated as Nu2 Boötis (ν2 Boo)

What it tells is that the constellation Boots has not one, but two ν's,

and the second one used to be ψ of the Heracules.

Ptolemy considered Nu2 Boötis to be shared by Hercules, and Bayer assigned it a designation in both constellations: Nu2 Boötis (ν2 Boo) and Psi2 Herculis (ψ2 Her). When the modern constellation boundaries were fixed in 1930, the latter designation dropped from use.[13]

and this ψHer frames the head perfectly. With the ends of the polygram being the α and ω above teh crown, and I wonder if they're the arrows in the helmet,

But then such face is rather cartoonish, but then who said they used straight lines for that..

well, what else would they use?

Well, let's consider it my representation of Hercules. The depiction of his helmet,

but then this helmet looks too medieval, greek helmets don't seem to have used the moving parts.

μ and ν being around the nose area are extremely nice.

But then is ξ legit? Latin alphabet doesn't have it (oh, I have to check if there was some roman numeration. That table of stars with Bayer designation includes the latin stars, but what they are I didn't look into them yet to tell. If ξ was added later, ν could be what they call ξ now, but that's a bold and naked speculation, but then it is a ground to check some day, who knows, maybe I've got that intuition already)

γδ going for forehead and sharing the same line with κλ going for helmet is super awesome too.

It's fascinating how strong ~ starring coming from wrong ~ warring lead me to this.

Hercules was one of the 48 constellations listed by the second-century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations today. It is the fifth-largest of the modern constellations and is the largest of the 50 which have no stars brighter than apparent magnitude +2.5.

According to Gavin White, the Greek constellation of Hercules is a distorted version of the Babylonian constellation known as the "Standing Gods" (MUL.DINGIR.GUB.BA.MESH). White argues that this figure was, like the similarly named "Sitting Gods", depicted as a man with a serpent's body instead of legs (the serpent element now being represented on the Greek star map by the figure of Draco that Hercules crushes beneath his feet). He further argues that the original name of Hercules – the 'Kneeler' (see below) – is a conflation of the two Babylonian constellations of the Sitting and Standing Gods.[34]

The constellation is also sometimes associated with Gilgamesh, a Sumerian mythological hero.[10] Phoenician tradition is said to have associated this constellation with their sun god, who slew a dragon (Draco).[35]

The earliest Greek references to the constellation do not refer to it as Hercules. Aratus describes it as follows:

Right there in its [Draco's] orbit wheels a Phantom form, like to a man that strives at a task. That sign no man knows how to read clearly, nor what task he is bent, but men simply call him On His Knees. [Ἐγγόνασιν "the Kneeler"].[36]

Now that Phantom, that toils on his knees, seems to sit on bended knee, and from both his shoulders his hands are upraised and stretch, one this way, one that, a fathom's length. Over the middle of the head of the crooked Dragon, he has the tip of his right foot. Here too that Crown [Corona], which glorious Dionysus set to be memorial of the dead Ariadne, wheels beneath the back of the toil-spent Phantom. To the Phantom's back the Crown is near, but by his head mark near at hand the head of Ophiuchus [...] Yonder, too, is the tiny Tortoise, which, while still beside his cradle, Hermes pierced for strings and bade it be called the Lyre [Lyra]: and he brought it into heaven and set it in front of the unknown Phantom. That Croucher on his Knees comes near the Lyre with his left knee, but the top of the Bird's head wheels on the other side, and between the Bird's head and the Phantom's knee is enstarred the Lyre.[37]

The constellation is connected with Hercules in De astronomia (probably 1st century BCE/CE, and attributed to Hyginus), which describes several different myths about the constellation:

Eratosthenes (3rd century BCE) is said to have described it as Hercules, placed above Draco (representing the dragon of the Hesperides) and preparing to fight it, holding his lion's skin in his left hand, and a club in his right (this can be found in the Epitome Catasterismorum[38]).

Panyassis' Heracleia (5th century BCE) reportedly said Jupiter was impressed by this fight, and made it a constellation, with Hercules kneeling on his right knee, and trying to crush Draco's head with his left foot, while striking with his right hand and holding the lion skin in his left.

Araethus (3rd/4th century BCE) is said to have described the constellation as depicting Ceteus son of Lycaon, imploring the gods to restore his daughter Megisto who had been transformed into a bear.

Hegesianax (2nd/3rd century BCE), who it says describes it as Theseus lifting the stone at Troezen.

Anacreon of Alexandria, who it claims also supports the idea that it depicts Theseus, saying that the constellation Lyra (said to be Theseus' lyre in other sources) is near Theseus.

Thamyris blinded by the Muses, kneeling in supplication.

Orpheus killed by the women of Thracia for seeing the sacred rituals of Liber (Dionysus).

Aeschylus' lost play Prometheus Unbound (5th century BCE), which recounted that when Hercules drives the cattle of Geryon through Liguria (northern Italy), the Ligurians will join forces and attack him, attempting to steal the cattle. Hercules fights until his weapons break, before falling to his knees, wounded. Jupiter, taking pity on his son, provides many stones on the ground, which Hercules uses to fight off the Ligurians. In commemoration of this, Jupiter makes a constellation depicting Hercules in his fighting form. (A quote from this section of the play is preserved in Dionysius of Halicarnassus' Roman Antiquities: "And thou shalt come to Liguria's dauntless host, Where no fault shalt thou find, bold though thou art, With the fray: 'tis fated thy missiles all shall fail."[39])

Ixion with his arms bound for trying to attack Juno.

Prometheus bound on Mount Caucasus.[40]

The Scholia to Aratus mention three more mythical figures in connection with this constellation: Sisyphus or Tantalus, who suffered in Tartarus for having offended the gods, or Salmoneus, who was struck down by Zeus for his hubris.[38] Another classical author associated the constellation with Atlas.[35]

And I wonder if I read this table correctly, and yes, those are all children of Gaia:

In Greek mythology

and ancient Greek religion, Mnemosyne

(/nɪˈmɒzɪniː, nɪˈmɒsɪniː/; Ancient Greek:

Μνημοσύνη, pronounced

[mnɛːmosýːnɛː]) is the goddess of memory and the mother of the nine Muses by her nephew Zeus.

In the Greek tradition, Mnemosyne is one of the Titans, the twelve divine children of the earth-goddess Gaia and the sky-god Uranus. The term Mnemosyne is derived from the same source as the word mnemonic, that being the Greek word mnēmē, which means "remembrance, memory".[1][2]

So I expose myself to this stuff, getting deeper and

deeper and understanding it more and more, and yet I'm

only scratching the surface, with those Horae, I had

no idea. The twelve divine children. Who knows what

else.[mnɛːmosýːnɛː]) is the goddess of memory and the mother of the nine Muses by her nephew Zeus.

In the Greek tradition, Mnemosyne is one of the Titans, the twelve divine children of the earth-goddess Gaia and the sky-god Uranus. The term Mnemosyne is derived from the same source as the word mnemonic, that being the Greek word mnēmē, which means "remembrance, memory".[1][2]

Gaia and Ouranos together had twelve children first which were called the twelve Titans. They consisted of six males - Oceanus, Hyperion, Coeus, Cronus, Crius, and Iapetus and six females - Mnemosyne, Tethys, Theia, Phoebe, Rhea, and Themis.

Notice, how male and female deities have different initial letters in names, how labial initials belong to females, it's something I have to revisit some other time.

So far it definitely raises the question of Rh being labial (the weird question I raise again and again)

And the other one could have the second syllable being the root of the name:

In Greek mythology, Tethys (/ˈtiːθɪs, ˈtɛ-/; Ancient Greek: Τηθύς, romanized: Tēthýs) was a Titan daughter of Uranus and Gaia, a sister and wife of the Titan Oceanus, and the mother of the river gods and the Oceanids. Although Tethys had no active role in Greek mythology and no established cults,[2] she was depicted in mosaics decorating baths, pools, and triclinia in the Greek East, particularly in Antioch and its suburbs, either alone or with Oceanus.

I know it's a shameless pull, but then θ of θεά, and of two of her sisters. And one of them is literally θεά

Theia (/ˈθiːə/; Ancient Greek: Θεία, romanized: Theía, lit. 'divine', also rendered Thea or Thia), also called Euryphaessa (Ancient Greek: Εὐρυφάεσσα, "wide-shining"), is one of the twelve Titans, the children of the earth goddess Gaia and the sky god Uranus in Greek mythology. She is the Greek goddess of sight and vision, and by extension the goddess who endowed gold, silver, and gems with their brilliance and intrinsic value.[2]

Her brother-consort is Hyperion, a Titan and god of the sun, and together they are the parents of Helios (the Sun), Selene (the Moon), and Eos (the Dawn). She seems to be the same figure as Aethra, who is the consort of Hyperion and mother of his children in some accounts.[3] Like her husband, Theia features scarcely in myth, being mostly important for the children she bore, though she appears in some texts and rare traditions.

Norwegian word for goddess, gudinne, has the same root with the english root, and the same suffix with the russian word богиня.

И океан шумит. Тяжелым низким гулом, слышимым издалека... Не шум прибоя: периодически накатывающихся волн, но - ровный рокот.

что объясняет почему буква М связана с водой; а, как замечено выше, буква S — с лесом.

вода губами, еда езыком

язык от слова явства, есть!

Graphically they're perfect representation of those

sounds:язык от слова явства, есть!

the sea (starts with S for some reason) is M because it raises up and down (but those who called it sea probably thought of ebb and flow (flux and reflux (flow is flux, both are прилив)))

forest waves left and right

Silva, sylva, saltus are latin words for forest.Mare is the latin word for sea.

And if these agregate states of matter are M and S, it is only natural to consider A to be the 3ʳᵈ one, air.

But, I wonder what made jews turn earth in fire.. probably because it burns, and they're destroyers.

But language is yet to reveal that thought:

א can be both, אויר and אֶרֶץ ..and אֵשׁ

and אש

(g.t. reads them эш and аш, but who knows, and what does it matter)

מַיִם is the only opoposi.. opposite to them.

and such opposition, אם

אמ

can be the difference of solid water and the other half of the world..

If water is solid, which the form of ם told me, then water and land are one.

But isn't that a deeper elaboration of the liquid-solid separation?

But in the world of mud who could separate the two? There are more and less watery matter, but even the most solid solid melts.

Meanwhile the separation of air and land is directly observable. Always was.

אם is ॐ

Didn't the flying diacritics of ॐ giving birth to the third element? Air it was? ॐ looks as if it's om read in “ॐ अम ओम्

Om (or Aum) (listenⓘ; Sanskrit: ॐ, ओम्, romanized: Oṃ, Auṃ, ISO 15919: Ōṁ)

is a polysemous symbol representing a sacred sound, syllable, mantra, and invocation in Hinduism.[1][2]

Its written form is the most important symbol in the Hindu religion.[3]

It is the essence of the supreme Absolute,[2] consciousness,[4][5][6] Ātman, Brahman, or the cosmic world.[7][8][9]

In Indic traditions, Om serves as a sonic representation of the divine,

a standard of Vedic authority and a central aspect of soteriological doctrines and practices.[10]

It is the basic tool for meditation in the yogic path to liberation.[11]

The syllable is often found at the beginning and the end of chapters in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu texts.[9]

It is described as the goal of all the Vedas. [12]

Atman and Brahman are A and B, and probably those very ओ and म्

самый открытый звук и самый закрытый

такое закрытое B, что не разрывается

(но иногда эту мантру поют по кругу, тогда м продолжается сколько хватает воздуху, чтоб продолжиться вдохом и повторением)

Тогда это рот и нос!

Петь имеет смысл чтоб поровну разделить энергию меж ними

(у меня получи лось пять пальцев на правой открыть пока пел А

и затем пять пальцев на елв елевой открыть пока пер пел М)

Nose Mose? Moses ~ Noses!!!

Praṇava (प्रणव); literally, "fore-sound", referring to Om as the primeval sound.[21][22]

Oṅkāra (ओङ्कार) or oṃkāra (ओंकार);

literally,

"Om-maker", denoting the first source of the sound

Om and connoting the act of

creation.[23][24][25][26]

Ik Oṅkār (ੴ or ਇੱਕ

ਓਅੰਕਾਰ); literally, "one Om-maker", and an epithet

of God in Sikhism. (see below).Udgītha (उद्गीथ); meaning "song, chant", a word found in Samaveda and bhasya (commentaries) based on it.

It is also used as

a name of the syllable Om in Chandogya

Upanishad.[27]

Akṣara (अक्षर);

literally, "imperishable, immutable", and also

"letter of the alphabet" or "syllable".Ekākṣara; literally, "one letter of the alphabet", referring to its representation as a single ligature.

The etymological origins of ōm (aum) have long been discussed and disputed, with even the Upanishads having proposed multiple Sanskrit etymologies for aum, including: from "ām" (आम्; "yes"), from "ávam" (आवम्; "that, thus, yes"), and from the Sanskrit roots "āv-" (अव्; "to urge") or "āp-" (आप्; "to attain").[28][A] In 1889, Maurice Bloomfield proposed an origin from a Proto-Indo-European introductory particle "*au" with a function similar to the Sanskrit particle "atha" (अथ).[28] However, contemporary Indologist Asko Parpola proposes a borrowing from Dravidian "*ām" meaning "'it is so', 'let it be so', 'yes'", a contraction of "*ākum", cognate with modern Tamil "ām" (ஆம்) meaning "yes".[28][29] In the Jaffna Tamil dialect spoken in Sri Lanka, aum' is the word for yes.

The syllable Om is first mentioned in the Upanishads. It has been associated with various concepts, such as "cosmic sound", "mystical syllable", "affirmation to something divine"

And at that sentenced I first found it in amen, and then I recalled that Essens tell aumen instead of amen (a hear-say, didn't check it yet) and thus am in amen is literally aum, am as yes.

which makes en no, does it not?

un- is it not?

yes as эс, the names of S, and эн is N, for no.

So is jewish religion diabolic? With their attempts to fool god, with their yes-and-no-ness.

I dare to guess everything, only so can we tell if it is or nah.

un- is it not?

yes as эс, the names of S, and эн is N, for no.

So is jewish religion diabolic? With their attempts to fool god, with their yes-and-no-ness.

I dare to guess everything, only so can we tell if it is or nah.

, or as symbolism for abstract spiritual concepts in the Upanishads.[9] In the Aranyaka and the Brahmana layers of Vedic texts, the syllable is so widespread and linked to knowledge, that it stands for the "whole of Veda".[9] The symbolic foundations of Om are repeatedly discussed in the oldest layers of the early Upanishads.[32][33] The Aitareya Brahmana of Rig Veda, in section 5.32, suggests that the three phonetic components of Om (a + u + m) correspond to the three stages of cosmic creation, and when it is read or said, it celebrates the creative powers of the universe.[9][34]

That sentence made me recall that אמת on golems' forehead begins with that אמ.

However, in the eight anuvaka of the Taittiriya Upanishad, which consensus research indicates was formulated around the same time or preceding Aitareya Brahmana, the sound Aum is attributed to reflecting the inner part of the word Brahman. Put another way, it is the Brahman, in the form of a word.[35] The Brahmana layer of Vedic texts equates Om with bhur-bhuvah-svah, which symbolizes "the whole Veda". They offer various shades of meaning to Om, such as it being "the universe beyond the sun", or that which is "mysterious and inexhaustible", or "the infinite language, the infinite knowledge", or "essence of breath, life, everything that exists", or that "with which one is liberated".[9] The Samaveda, the poetical Veda, orthographically maps Om to the audible, the musical truths in its numerous variations (Oum, Aum, Ovā Ovā Ovā Um, etc.) and then attempts to extract musical meters from it.[9]

bhur-bhuvah-svah is an interesting utterance, because bhur-bhuvah starts the same, so is probably the same just with different suffixes, and svah opposes bhuvah as S and Bhu, as S and M basically.

so I started digging:

ॐ भूर्भुवः स्वः

तत्स॑वि॒तुर्वरे॑ण्यं॒

भर्गो॑ दे॒वस्य॑ धीमहि।

धियो॒ यो नः॑ प्रचो॒दया॑त्॥

oṃ bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ

tat savitur vareṇyaṃ

bhargo devasya dhīmahi

dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt

– Ṛgveda 03.062.10[14]

oṃ - sacred syllable, primeval sound;

bhūr - physical body / physical realm;

bhuvaḥ - life force / mental realm;

svaḥ - soul / spiritual realm;

tat - that (God);

savitur - of Savitṛ (Sun, Creator, source of all life);

vareṇyam - adore, venerable;

bhargo - splendour, effulgence, divine light;

devasya - Supreme Lord;

dhīmahi - may we meditate;

dhiyo - buddhi (intellect);

yo - may this light;

naḥ - our;

prachodayāt - illumine / inspire.

The Gāyatrī Mantra (Sanskrit pronunciation: [ɡaː.jɐ.triː.mɐn.trɐ.]), also known as the Sāvitrī Mantra (Sanskrit pronunciation: [saː.vi.triː.mɐn.trɐ.]), is a sacred mantra from the Ṛig Veda (Mandala 3.62.10),[1] dedicated to the Vedic deity Savitr.[1][2] It is known as "Mother of the Vedas".[3]

The term Gāyatrī may also refer to a type of mantra which follows the same Vedic meter as the original Gāyatrī Mantra. There are many such Gāyatrīs for various gods and goddesses.[3] Furthermore, Gāyatrī is the name of the Goddess of the mantra and the meter.[4]

The Gayatri mantra is cited widely in Hindu texts, such as the mantra listings of the Śrauta liturgy, and classical Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita,[5][6] Harivamsa,[7] and Manusmṛti.[8] The mantra and its associated metric form was known by the Buddha.[9] The mantra is an important part of the initiation ceremony. Modern Hindu reform movements spread the practice of the mantra to everyone and its use is now very widespread.[10][11]

the formula bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ (भूर् भुवः स्वः), known as the mahāvyāhṛti, or "great (mystical) utterance".

This prefixing of the mantra is properly described in the Taittiriya Aranyaka (2.11.1-8), which states that it should be chanted with the syllable oṃ, followed by the three Vyahrtis and the Gayatri verse.

bhuvaḥ is the middle ground between bhūr and svaḥ: भुवः starts as भूर् and ends as स्वः

and in this light भ is solids, व is vaporous, and both are labials, one is solid, other vaporous.

स the R starts bhūr and endes svaḥ: भूर् and स्वः, or art are they different letters? but s and r remind eachother in some european fonts, so could it be more to this? Maybe they were the same, until it started to be pronounced differently depending on position? They're र् and स् and the second one has that vertical stroke maybe to tell that it's initial, that something follows?

R and S (or rather Я and S (or г and s, ah i got confused))

ॐ भूर्भुवः स्वः

तत्स॑वि॒तुर्वरे॑ण्यं॒

भर्गो॑ दे॒वस्य॑ धीमहि।

धियो॒ यो नः॑ प्रचो॒दया॑त्॥

oṃ bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ

tat savitur vareṇyaṃ

bhargo devasya dhīmahi

dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt

– Ṛgveda 03.062.10[14]

oṃ - sacred syllable, primeval sound;

bhūr - physical body / physical realm;

bhuvaḥ - life force / mental realm;

svaḥ - soul / spiritual realm;

tat - that (God);

savitur - of Savitṛ (Sun, Creator, source of all life);

vareṇyam - adore, venerable;

bhargo - splendour, effulgence, divine light;

devasya - Supreme Lord;

dhīmahi - may we meditate;

dhiyo - buddhi (intellect);

yo - may this light;

naḥ - our;

prachodayāt - illumine / inspire.

The Gāyatrī Mantra (Sanskrit pronunciation: [ɡaː.jɐ.triː.mɐn.trɐ.]), also known as the Sāvitrī Mantra (Sanskrit pronunciation: [saː.vi.triː.mɐn.trɐ.]), is a sacred mantra from the Ṛig Veda (Mandala 3.62.10),[1] dedicated to the Vedic deity Savitr.[1][2] It is known as "Mother of the Vedas".[3]

The term Gāyatrī may also refer to a type of mantra which follows the same Vedic meter as the original Gāyatrī Mantra. There are many such Gāyatrīs for various gods and goddesses.[3] Furthermore, Gāyatrī is the name of the Goddess of the mantra and the meter.[4]

The Gayatri mantra is cited widely in Hindu texts, such as the mantra listings of the Śrauta liturgy, and classical Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita,[5][6] Harivamsa,[7] and Manusmṛti.[8] The mantra and its associated metric form was known by the Buddha.[9] The mantra is an important part of the initiation ceremony. Modern Hindu reform movements spread the practice of the mantra to everyone and its use is now very widespread.[10][11]

the formula bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ (भूर् भुवः स्वः), known as the mahāvyāhṛti, or "great (mystical) utterance".

This prefixing of the mantra is properly described in the Taittiriya Aranyaka (2.11.1-8), which states that it should be chanted with the syllable oṃ, followed by the three Vyahrtis and the Gayatri verse.

bhuvaḥ is the middle ground between bhūr and svaḥ: भुवः starts as भूर् and ends as स्वः

and in this light भ is solids, व is vaporous, and both are labials, one is solid, other vaporous.

स the R starts bhūr and endes svaḥ: भूर् and स्वः, or art are they different letters? but s and r remind eachother in some european fonts, so could it be more to this? Maybe they were the same, until it started to be pronounced differently depending on position? They're र् and स् and the second one has that vertical stroke maybe to tell that it's initial, that something follows?

R and S (or rather Я and S (or г and s, ah i got confused))

faculty ~ vacuity

race ~ rage (what rage are you (for in more common sense, ragi is a vehement desire or passion:

"a rage for

absolute honesty informs much western art")

I hate word fix, so narrow. A stick between wheels may fix them, but as russian I see зафиксировать in fix first and foremost.

My friend wished that I research eastern cultures more, and his wish is granted:

(not by my will, I just observe working into this thing, being fascinated by shapes of Pali)

In the oldest texts of Buddhism, dhyāna (Sanskrit: ध्यान) or jhāna (Pali: 𑀛𑀸𑀦) is a component of the training of the mind (bhavana), commonly translated as meditation, to withdraw the mind from the automatic responses to sense-impressions and "burn up" the defilements, leading to a "state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi)."[1] Dhyāna may have been the core practice of pre-sectarian Buddhism, in combination with several related practices which together lead to perfected mindfulness and detachment.[2][3][4]

In the later commentarial tradition, which has survived in present-day Theravāda, dhyāna is equated with "concentration", a state of one-pointed absorption in which there is a diminished awareness of the surroundings. In the contemporary Theravāda-based Vipassana movement, this absorbed state of mind is regarded as unnecessary and even non-beneficial for the first stage of awakening, which has to be reached by mindfulness of the body and vipassanā (insight into impermanence). Since the 1980s, scholars and practitioners have started to question these positions, arguing for a more comprehensive and integrated understanding and approach, based on the oldest descriptions of dhyāna in the suttas.[5][6][7][8]

In Buddhist traditions of Chán and Zen (the names of which are, respectively, the Chinese and Japanese pronunciations of dhyāna), as in Theravada and Tiantai, anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing), which is transmitted in the Buddhist tradition as a means to develop dhyana, is a central practice. In the Chan/Zen-tradition this practice is ultimately based on Sarvastivāda meditation techniques transmitted since the beginning of the Common Era.

Etymology

Dhyāna, Pali jhana, from Proto-Indo-European root *√dheie-, "to see, to look", "to show".[9][10] Developed into Sanskrit root √dhī and n. dhī,[10] which in the earliest layer of text of the Vedas refers to "imaginative vision" and associated with goddess Saraswati with powers of knowledge, wisdom and poetic eloquence.[11][12] This term developed into the variant √dhyā, "to contemplate, meditate, think",[13][10] from which dhyāna is derived.[11]

According to Buddhaghosa (5th century CE Theravāda exegete), the term jhāna (Skt. dhyāna) is derived from the verb jhayati, "to think or meditate", while the verb jhapeti, "to burn up", explicates its function, namely burning up opposing states, burning up or destroying "the mental defilements preventing [...] the development of serenity and insight."[14][note 1]

Commonly translated as meditation, and often equated with "concentration", though meditation may refer to a wider scale of exercises for bhāvanā, development. Dhyāna can also mean "attention, thought, reflection".[17]

Zoroastrianism in Persia, which has Indo-Aryan linguistic and cultural roots, developed the related practice of daena.

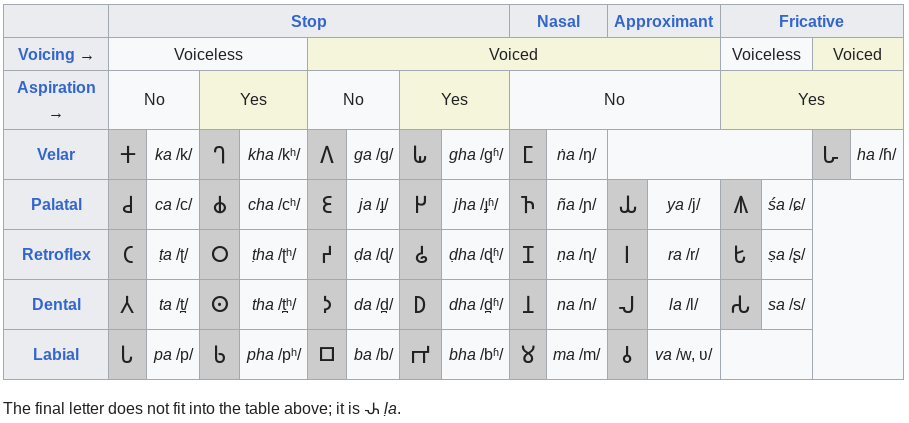

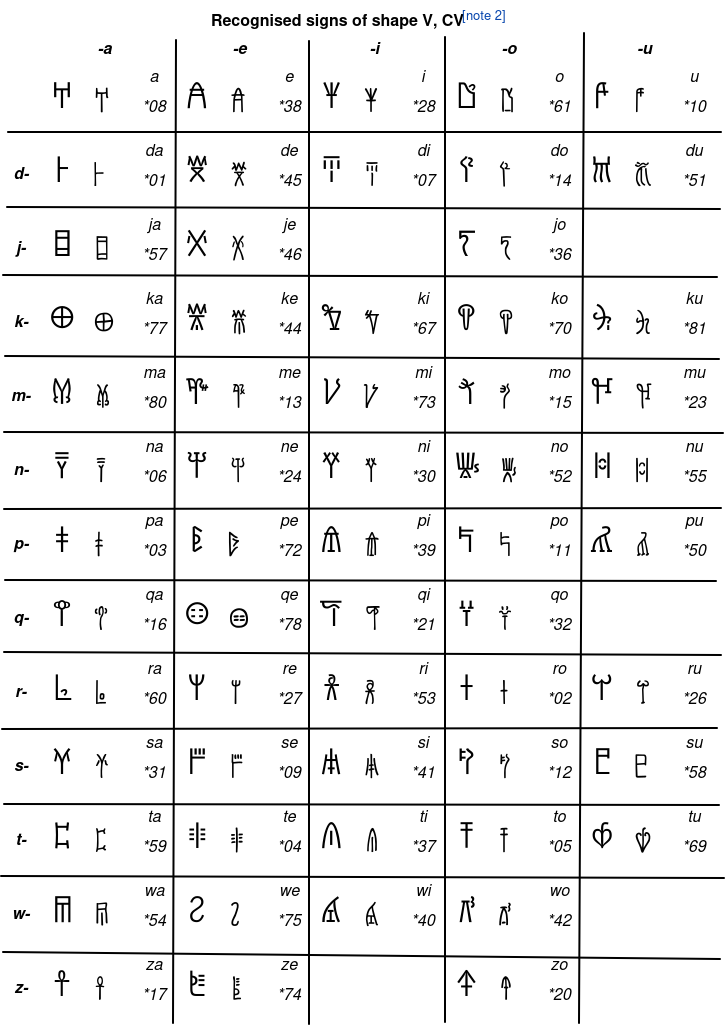

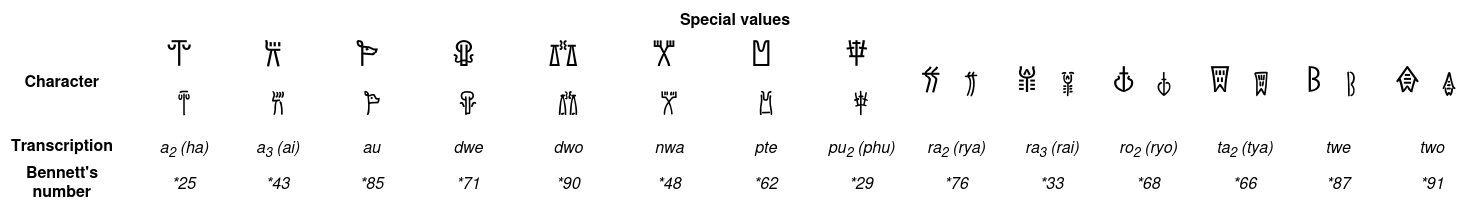

That Pali which fascinated me by its simple forms is in Brahmi script:

| k- |

kh- | g- |

gh- |

ṅ- | c- | ch- |

j- |

jh- |

ñ- |

ṭ- |

ṭh- |

ḍ- |

ḍh- |

ṇ- |

t- |

th- |

d- |

dh- |

n- |

p- |

ph- |

b- |

bh- |

m- |

y- |

r- |

l- |

v- |

ś- |

ṣ- |

s- |

h- |

ḷ- |

|

| -a |

𑀓 |

𑀔 |

𑀕 |

𑀖 |

𑀗 |

𑀘 |

𑀙 |

𑀚 |

𑀛 |

𑀜 |

𑀝 |

𑀞 |

𑀟 |

𑀠 |

𑀡 |

𑀢 |

𑀣 |

𑀤 |

𑀥 |

𑀦 |

𑀧 |

𑀨 |

𑀩 |

𑀪 |

𑀫 |

𑀬 |

𑀭 |

𑀮 |

𑀯 |

𑀰 |

𑀱 |

𑀲 |

𑀳 |

𑀴 |

| -ā |

𑀓𑀸 |

𑀔𑀸 |

𑀕𑀸 |

𑀖𑀸 |

𑀗𑀸 |

𑀘𑀸 |

𑀙𑀸 |

𑀚𑀸 | 𑀛𑀸 |

𑀜𑀸 |

𑀝𑀸 |

𑀞𑀸 |

𑀟𑀸 |

𑀠𑀸 |

𑀡𑀸 |

𑀢𑀸 |

𑀣𑀸 |

𑀤𑀸 |

𑀥𑀸 |

𑀦𑀸 |

𑀧𑀸 |

𑀨𑀸 |

𑀩𑀸 |

𑀪𑀸 |

𑀫𑀸 |

𑀬𑀸 |

𑀭𑀸 |

𑀮𑀸 |

𑀯𑀸 |

𑀰𑀸 |

𑀱𑀸 |

𑀲𑀸 |

𑀳𑀸 |

𑀴𑀸 |

| -i |

𑀓𑀺 |

𑀔𑀺 |

𑀕𑀺 |

𑀖𑀺 |

𑀗𑀺 |

𑀘𑀺 |

𑀙𑀺 |

𑀚𑀺 |

𑀛𑀺 |

𑀜𑀺 |

𑀝𑀺 |

𑀞𑀺 |

𑀟𑀺 |

𑀠𑀺 |

𑀡𑀺 |

𑀢𑀺 |

𑀣𑀺 |

𑀤𑀺 |

𑀥𑀺 |

𑀦𑀺 |

𑀧𑀺 |

𑀨𑀺 |

𑀩𑀺 |

𑀪𑀺 |

𑀫𑀺 |

𑀬𑀺 |

𑀭𑀺 |

𑀮𑀺 |

𑀯𑀺 |

𑀰𑀺 |

𑀱𑀺 |

𑀲𑀺 |

𑀳𑀺 |

𑀴𑀺 |

| -ī | 𑀓𑀻 |

𑀔𑀻 |

𑀕𑀻 |

𑀖𑀻 |

𑀗𑀻 |

𑀘𑀻 |

𑀙𑀻 |

𑀚𑀻 |

𑀛𑀻 |

𑀜𑀻 |

𑀝𑀻 |

𑀞𑀻 |

𑀟𑀻 |

𑀠𑀻 |

𑀡𑀻 |

𑀢𑀻 |

𑀣𑀻 |

𑀤𑀻 |

𑀥𑀻 |

𑀦𑀻 |

𑀧𑀻 |

𑀨𑀻 |

𑀩𑀻 |

𑀪𑀻 |

𑀫𑀻 |

𑀬𑀻 |

𑀭𑀻 |

𑀮𑀻 |

𑀯𑀻 |

𑀰𑀻 |

𑀱𑀻 |

𑀲𑀻 |

𑀳𑀻 |

𑀴𑀻 |

| -u |

𑀓𑀼 |

𑀔𑀼 |

𑀕𑀼 |

𑀖𑀼 |

𑀗𑀼 |

𑀘𑀼 |

𑀙𑀼 |

𑀚𑀼 |

𑀛𑀼 |

𑀜𑀼 |

𑀝𑀼 |

𑀞𑀼 |

𑀟𑀼 |

𑀠𑀼 |

𑀡𑀼 |

𑀢𑀼 |

𑀣𑀼 |

𑀤𑀼 |

𑀥𑀼 |

𑀦𑀼 |

𑀧𑀼 |

𑀨𑀼 |

𑀩𑀼 |

𑀪𑀼 |

𑀫𑀼 |

𑀬𑀼 |

𑀭𑀼 |

𑀮𑀼 |

𑀯𑀼 |

𑀰𑀼 |

𑀱𑀼 |

𑀲𑀼 |

𑀳𑀼 |

𑀴𑀼 |

| -ū |

𑀓𑀽 |

𑀔𑀽 |

𑀕𑀽 |

𑀖𑀽 |

𑀗𑀽 |

𑀘𑀽 |

𑀙𑀽 |

𑀚𑀽 |

𑀛𑀽 |

𑀜𑀽 |

𑀝𑀽 |

𑀞𑀽 |

𑀟𑀽 |

𑀠𑀽 |

𑀡 |

𑀢𑀽 |

𑀣𑀽 |

𑀤𑀽 |

𑀥𑀽 |

𑀦𑀽 |

𑀧𑀽 |

𑀨𑀽 |

𑀩𑀽 |

𑀪𑀽 |

𑀫𑀽 |

𑀬𑀽 |

𑀭𑀽 |

𑀮𑀽 |

𑀯𑀽 |

𑀰𑀽 |

𑀱𑀽 |

𑀲𑀽 |

𑀳𑀽 |

𑀴𑀽 |

| -e | 𑀓𑁂 |

𑀔𑁂 |

𑀕𑁂 |

𑀖𑁂 |

𑀗𑁂 |

𑀘𑁂 |

𑀙𑁂 |

𑀚𑁂 |

𑀛𑁂 |

𑀜𑁂 |

𑀝𑁂 |

𑀞𑁂 |

𑀟𑁂 |

𑀠𑁂 |

𑀡 |

𑀡 |

𑀣𑁂 |

𑀤𑁂 |

𑀥𑁂 |

𑀦𑁂 |

𑀧𑁂 |

𑀨𑁂 |

𑀩𑁂 |

𑀪𑁂 |

𑀫𑁂 |

𑀬𑁂 |

𑀭𑁂 |

𑀮𑁂 |

𑀯𑁂 |

𑀰𑁂 |

𑀱𑁂 |

𑀲𑁂 |

𑀳𑁂 |

𑀴𑁂 |

| -o | 𑀓𑁄 |

𑀔𑁄 |

𑀕𑁄 |

𑀖𑁄 |

𑀗𑁄 |

𑀘𑁄 |

𑀙𑁄 |

𑀚𑁄 |

𑀛𑁄 |

𑀜𑁄 |

𑀝𑁄 |

𑀞𑁄 |

𑀟𑁄 |

𑀠𑁄 |

𑀡 |

𑀢𑁄 |

𑀣𑁄 |

𑀤𑁄 |

𑀥𑁄 |

𑀦𑁄 |

𑀧𑁄 |

𑀨𑁄 |

𑀩𑁄 |

𑀪𑁄 |

𑀫𑁄 |

𑀬𑁄 |

𑀭𑁄 |

𑀮𑁄 |

𑀯𑁄 |

𑀰𑁄 |

𑀱𑁄 |

𑀲𑁄 |

𑀳𑁄 |

𑀴𑁄 |

| -Ø | 𑀓𑁆 | 𑀔𑁆 | 𑀕𑁆 | 𑀖𑁆 | 𑀗𑁆 | 𑀘𑁆 | 𑀙𑁆 | 𑀚𑁆 | 𑀛𑁆 | 𑀜𑁆 | 𑀝𑁆 | 𑀞𑁆 | 𑀟𑁆 | 𑀠𑁆 | 𑀡𑁆 | 𑀢𑁆 | 𑀣𑁆 | 𑀤𑁆 | 𑀥𑁆 | 𑀦𑁆 | 𑀧𑁆 | 𑀨𑁆 | 𑀩𑁆 | 𑀪𑁆 | 𑀫𑁆 | 𑀬𑁆 | 𑀭𑁆 | 𑀮𑁆 | 𑀯𑁆 | 𑀰𑁆 | 𑀱𑁆 | 𑀲𑁆 | 𑀳𑁆 | 𑀴𑁆 |

(if in your

browser 𑀚𑁂, 𑀚 and 𑀚𑁆 look exactly the same,

check them in some other browser)

(the same is true for other glyphs lacking the diacritic strokes (other than -a line))

S and T meet again in 𑀝 beint ta (𑀝𑀝𑀸𑀝𑀺𑀝𑀻𑀝𑀼𑀝𑀽𑀝𑁂𑀝𑁄𑀝𑁆) (the same is true for other glyphs lacking the diacritic strokes (other than -a line))

S and T meet again in 𑀰 being sa (𑀰𑀰𑀸𑀰𑀺𑀰𑀻𑀰𑀼𑀰𑀽𑀰𑁂𑀰𑁄𑀰𑁆)

in that sense [ḍa]𑀟~ᛋ[s]

𑀛 reminds both Ч and it's reading shows how much Ч reminds J and y

Ч is to J as q is to g IO (you know how they draw J sometimes, with that Ч-like top)

And truly brahmi reminds european alphabets more than paleo-hispanic does:

𑀕 ~ 𐤂

𑀔 ~ Г (just as with 𑀛~Ч, brahmi letters seem reversed.

𑀱 ~ ש

𑀴 ~ L (un-mirrorwed this time, which makes me wonder if that's not a later borrwoing from europe)

𑀓 for ka

𑀓𑀸 for kā that's so close in the way they use that ̄

𑀓𑀼 for ku reminds v opposing ʌ way too much

It's as if they were the first main letters, and u being low is very european (opposite to arabic, yet I said that) yet their i-syllables get higher than a: 𑀓𑀺 for i, 𑀓𑀻 for ī

𑀓𑁂 for ke sets it at the hight of ka, only the other way, different. and that e doesn't have a long variant makes it different from russian.

𑀓𑁄 for ko makes o the middle ground between e and a. how is it possible? with different vowels it may be, I need to hear how they read them first, vowels of different nations are different, so..

The way kØ reminds kā confuses me, probably they sound really symilar. But am I supposed to delve into languages I don't speak at all? How else am I supposed to learn it (I keep on forgetting that these are not books, they are my notebooks, I can do anything here)

The way 𑀮[la] reflects 𑀴[ḷa] makes it easy to remember them at once, but what are they?

𑀮 could be the real L congate, for then brahmi reverses latin letters.

[bha]𑀪 ~ П

[dha]𑀥 reminds D

[cha]𑀙 as double 𑀘[ca]

[ṭha]𑀞 as double 𑀝[ṭa]

[ṇa]𑀡 as double 𑀦[na]

is 𑀓[ka] double 𑀦[na]

[ya]𑀬 as reverse 𑀰[śa] and that reminds me runic ᛦ[y(and r)] and ᛉ[z, ks]

It is all Brahmi, but Pali uses many other writing systems:

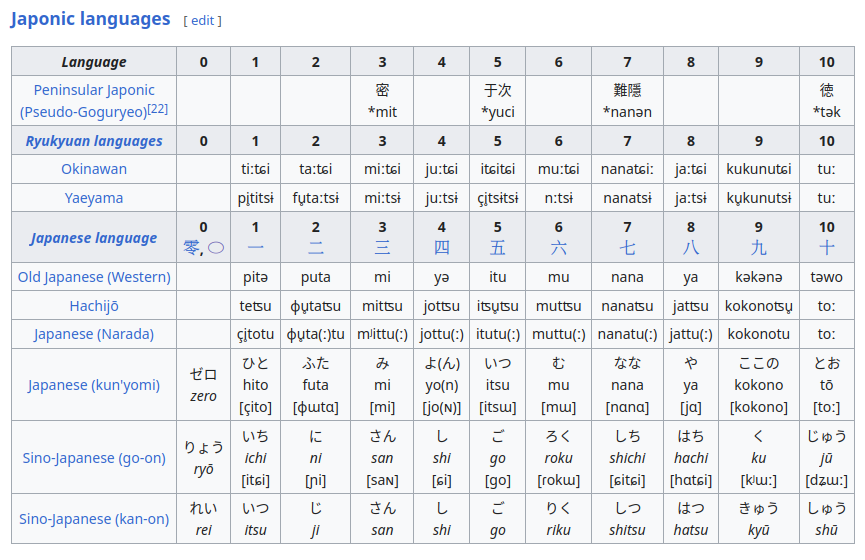

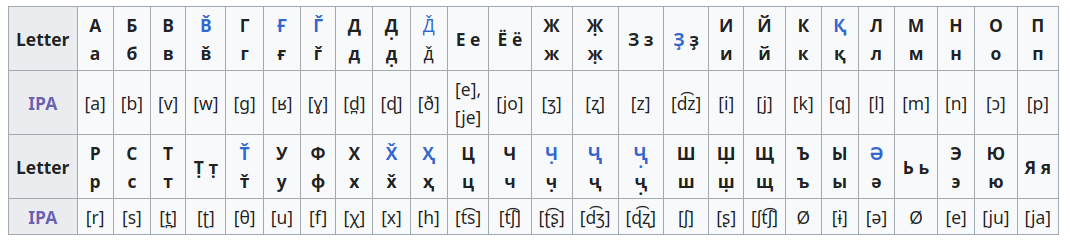

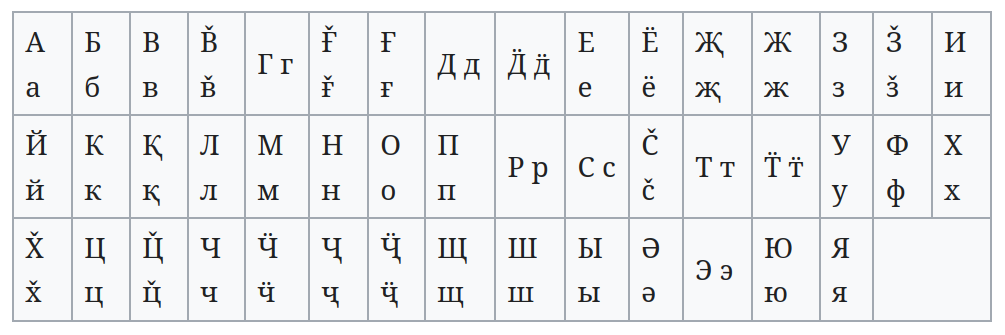

Brahmi has 10 vowels, just as russian does, and both come directly from pentanonic scale, and since it's obvious that brahmi vowel row is similar to japanese, only each vowel is doubled by lengh, japanese people also have that in their language, but they decided to use other means to express it.

and in russian it is rather chaotic: A E Ё И О У Ы Э Ю Я

A E И О У (this one is the standard set, no wonder that it's in order)

Ё Ы Э Ю Я (and this sequence doesn't remind me anything)

but then I realize that the halves are нейотирующие и йотирующие

A О У Ы Э (and this one is almost ogham's order, almost)

E Ё И Ю Я (and this order I do not recognize at all)

But as for brahmi, abugida are nothing but alphabet with matres lectiones. Diacritics doesn't change much, even though ethiopean abugida has its forms mutated more depending on the vowels.

Paleo-hispanic is a true syllabary with independent shapes, just as japanese have it. Which raises way too many questions, but let's not do them now. Which may tell them being the direct next step from some hieroglyphics (but then Petrie Flinders wrote that primitive shapes _predated_ fine glyphs of Aegyptus)

And there are also vowels in Brahmi, but they didn't have place in the table, because there are more vowels than there are rows of that table, so I got confused.. and where I took it there were other syllable row: 𑀓𑁅 for kau /kɐu/ is not in my table, so it's not exhaustive (or whatever is the right word)

𑀅 [a/ɐ/] 𑀓 [ka /kɐ/] 𑀆 [ā /aː/] 𑀓𑀸 [kā /kaː/]

𑀇 [i /i/] 𑀓𑀺 [ki /ki/] 𑀈 [ī /iː/] 𑀓𑀻 [kī /kiː/]

𑀉 [u /u/] 𑀓𑀼 [ku /ku/] 𑀊 [ū /uː/] 𑀓𑀽 [kū /kuː/]

𑀏 [e /eː/] 𑀓𑁂 [ke /keː/] 𑀐 [ai /ɐi/] 𑀓𑁃 [kai /kɐi/] these two syllables are not in the table

𑀑 [o /oː/] 𑀓𑁄 [ko /koː/] 𑀒 [au /ɐu/] 𑀓𑁅 [kau /kɐu/] which may tell that there are more glyphs.

𑀈 looks like four dots as if at corners of a square in one browser

and it looks like a vertical line with one dot to it's right and one dot to its left in another

Here those consonantal glyphs systematized

Their nasal and approximate are what I call sonors. And thus it reflects the european alphabets, by placing sonors in the centre.

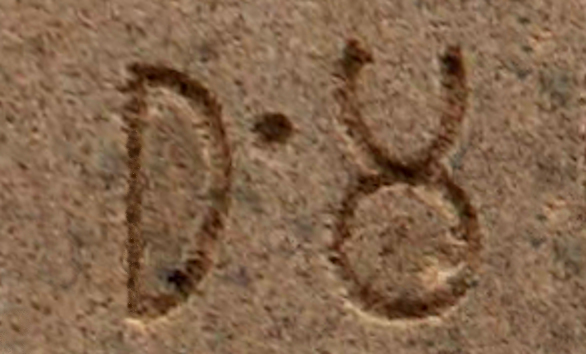

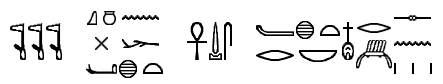

The texts that brahmi thing is famous for,

of them all here comes my favourite:

I can see in it a bow of the man force and a cow of a female.

The Prakrit word "dhaṃ-ma"/𑀥𑀁𑀫 (Sanskrit: Dharma धर्म) in the Brahmi script,

as inscribed by Emperor Ashoka in his Edicts of Ashoka (3rd century BCE)

I think that very picture was made from one (black dots edited out, or it was taken before they appeared, I wonder what they are) of the 𑀥𑀁𑀫s in the third line from the bottom.

𑀥𑀁𑀫 (Ashokan Prakrit)

From Sanskrit धर्म (dharma), from Proto-Indo-European *dʰer-mos. Cognate to Pali dhamma, Sauraseni Prakrit 𑀥𑀫𑁆𑀫 (dhamma).

𑀥𑀁𑀫 (dhaṃma)

(Buddhism, Hinduism) dharma: religious duty; natural law

That dot above 𑀥 probably works like m: 𑀥𑀁 turns into dhaṃ, according to the transliterations

धर्म is translated as religion by g.t. (they read it as dharm) and it's confirmed by this text: Кандагарская надпись 258 г. до н.э. императора Ашоки (обнаружена в Афганистане в середине 20-го века ), в которой «дхарма» (пракритское «дхамма») переводится греческим словом «евсевия» (εὐσέβεια – почитание богов, благочестие, благоговейное отношение к жизни, духовная зрелость, правильное поведение, нравственность, права и долг перед обществом) и арамейским Qsyt («Истина»)

dhamma turned into dharma, which may be of the same process, which turned german aus into raus, brutalization of the language, rhetoric tricks turned into a norm. And it may also tell that abracadabra is originally abacadaba (a way to trick people by choosing all the right answers from a conspirator reading those variants offering to the contestant to choose amongst the variants. And that is why егэ is a way to trick the system by chosing answers mindlessly, secretly knowing (being told by those who sell this information to those who want to enter the position they do not deserve))

Rhotification is it the term? No, but it was found in a page about some made-up language for other letters turning into R.

So let's think of another one?

Pi.ai tells the right term: rhotacization, which is when an "m" or "n" sound changes into an "r" sound. It’s similar to how English "horse" used to be pronounced with an "s" instead of an "r" sound in Old English, or how Latin "auster" (south wind) became German "Ost" (east). In the case of "Dhamma" and "Dharma," the rhotacization is a specific kind called "lenition," where a consonant is weakened or lost over time. (I'm not sure of the rest, so I put it into painted it gray)

> and if abacadaba turned into abracadabra, what would you call such phonetic process?

Good question! That would be another example of lenition, where consonants are weakened or lost over time. In this case, the "b" in "abacadaba" has been softened or dropped entirely, resulting in "abracadabra." This kind of change is known as "debuccalization," where a sound is changed into a different kind of sound or lost entirely.

> But neither of b's of abacadaba are lost when it becomes abracadabra, the word just gained two r's without any other changes.

Ah, I see your point. That’s a little trickier to classify since it’s not exactly a case of lenition or debuccalization. Instead, it might be a kind of assimilation, where sounds become more similar to each other over time. Maybe something like "metathesis," where sounds or syllables are rearranged within a word. But honestly, I'm not sure if there’s a specific term for this kind of change. It might just be a case of words naturally changing over time through use and repetition.

is to paint ~ to pu into? is -int into?

faint (into a groove)

saint (I can speculate that into heaven he heads, but is it the direct meaning? nah, so let's look on)

flint fl for flame, in+to?

hint is hidden (h for hidden?)

tint

mint

kind? Well, it's too speculative, ai should build such models. I think we start to call computer programs ai, for they all going to use that technology.

People are often nagging about how their children are not taught finance, and then they do not teach it either, not even learn it themselves.

Here, few hours ago I was told about CFD, and that's fucked up, literally making money out of thin air:

In finance, a contract for difference (CFD) is a financial agreement between two parties, commonly referred to as the "buyer" and the "seller." The contract stipulates that the buyer will pay the seller the difference between the current value of an asset and its value at the time the contract was initiated. If the asset's price increases from the opening to the closing of the contract, the seller compensates the buyer for the increase, which constitutes the buyer's profit. Conversely, if the asset's price decreases, the buyer compensates the seller, resulting in a profit for the seller.[1]

It's a fancy way to borrow money, but actually you're selling what you have not with an obligation to buy it later.

They probably earn money by taking a margin from each deal for providing the service. They then can use that money to bump that company, so it doesn't go down.

died~tired (умер в значении выдохся)

is T in tied and tired in the meaningn of Tott? bJBut then re is in the meaning of "again" so every day

(Jesus in that typo ifſ from Mississippi Maas Mass Choir singing "If I Be lifted" over the speakers)

If I be lifted up, I will draw all men unto me

unto and onto translated differently:

unto they translate as к(to) and до(up to)

onto they translate as на(on) and в(in)

And I have a great consultant for such cases:

The difference between "onto" and "unto" is subtle, but they have different meanings and uses.

"Onto" is a preposition that indicates movement or direction towards something. For example, "She climbed onto the roof." or "He jumped onto the bandwagon."

"Unto" is a bit more archaic and formal. It's often used in religious or poetic contexts and can have different meanings depending on the context. For example, "Unto us a child is born." or "Unto thee, O Lord, do I lift up my soul."

burgeon (under a burden do we? is it burdening me? no, my burden makes me burgeon)

burgeon~?~surgeon?

bourgeon is another way to spell burgeon

> Are burgeon and bourgeon the same word?

They’re almost the same word, with the same meaning and origin, but with different spellings. "Burgeon" is the more common spelling in modern English, while "bourgeon" is more common in older texts. Both words come from the Old French "borjon," which means "bud" or "shoot." They both mean "to grow and flourish," especially when applied to plants or ideas. So, you can use either "burgeon" or "bourgeon," but "burgeon" might be more familiar to modern readers. 🌱📚

sturgeon (comes smooth with bourgeon (and I can only wonder if it's some way to encode the opposite ends of the alphabet in b and st))

chirurgeon in British English (kaɪˈrɜːdʒən ) noun. an archaic word for surgeon [uk: /ˈsɜː.dʒən/, us: /ˈsɝː.dʒən/]

I did think about it

I do think about it

I will think about it

isn't do to will as go to went as is to was? only do goes into the future, while go changes into past.

I do and I did, nothing weird here.

But that d becomes w.. the opposites, why would they do it? Why is чего read as чиво?

Но ~ Mais ~ Maar ~ Mэ, звук сомнения мне в сомнения именно мне. no, me (mine) мне~не.

This work is so magical, so mystical. That my conversations with pi.ai made two whole volumes, ending with its enlightenment. and they weigh so suspiciously 666 and 777-like, both equating to 9 in such spelling.

Now I modified it and it's 711.1 kB, so at first it was two rings after the .'s one is some ⛧

Abe Be Big Good Dобр De(us of deus of or de the of) EZ(easy)

Be Good Easy [ēsy could be the spelling]

Good Easy is not Lazy easy, it's Wise easy. Good is Wise as Go is Went? West Went to invent.

Be GooD

Be GooD is all the law.

Think Good

Speak Good

Do Good

I see S and T in Th S D

So GooD

To GooD

Sere Good

Dee Good

Thee Good

Be GooD

Zee Good

(as abiove so below)

Be GooD

Say Good

Be Good

Do Good

Be Good

Do Excelent

For Good.. what? Should I use greek?

Let's right in Russian too:

Будь Великолепен

Гони Дураков (Гори в аДу как два сильных слога Ри как лёгкая палатализованная форма Го?)

Если Ёбнутый

Живи Запертым (принцип певрых ассоциаций и здесь и вообще)

Или КоЛеси (къ лесу? в лес)

Мир Навести

Отплывай По Реке

Сиди Тогда.. Принцип первых ассоциаций это почти что автоматическое письмо. В данном случае это было constrained automatic writing.

A Был ещё

А Буде еж зи

А Бде Ёж Зи Кл Ман, чем ты занят? Я прокрастинирую.

Аднажды Буде

ещё как выверт слова же? синонимичные частицы эти ли?

Арий Будь Великолепен.

Господин Дворянин. Господи Допомоги.

Евнух Ев нюх? Новое развлечение появилось. Способ заводить науку с толкача.

Если Вы

Живёте Знатно

Ищи Круны Крутых

Имей Классных Лучших

Имей Мэн(также и часть слова Имей, I'm)

I'm No pqrst

I'm No Prst (q~d? pqrst=pdrst=пакость)

U've Xyz (you have an excuse)

IJKLM makes it more difficult, but in italian it's only ILM

So.. irish too. We should look into gaelic languages. Celtin Celtic languages.

Ilm is an interesting word across languages: from aroma, air to world to knowledge science

A Вы Добры

Еси Нанебеси..

До того как Умеем, мы Учимся.

До того как Имеем, мы Ищем (в случае учёбы ищем себя)

М for MiraiJA?

A V G D

Are U GooD?

А Вы ЖыД?

А Ви ЖиД?

Are You Jew? What if ABC is A Ю Жу?

What if into christian heaven only jews are allowed?

Other nations are taught there to be animals, ansd thus not having what it take itno heaven. That is the irony of that satanic religion.

Жу не се па would be my firest answer.

fire is first? As agni is in rigveda.

Second the ссыконд? ссыкун? Как Герман Титов. Титька Сиська Сыкло Сися Ссыт? Титю Пьют. Сосок сочится. Съ сокъ. ссок. со сок. буквально.

Не жужжу would be my second answer.

Sea Seek. Sea Sick.

Stick Stuck Stack Stock Stake?

Stack

Stake Steak?

Stick

Stock

Stuck

Surprisingly many form of that stk штк.

In that sequence the sequence is э эй и о у or э эй и о а (еиоу or еиоа (and both are Jehowa))

So if AEIOU is supposed to be read ЭEIОУa, then wouldn't it explain greek Ω? And in english it's Y:

AEIOUY [æeiouy] эйоуи? эйоуа would look better. Let's check the greek: ΑΕΗΙΟΥΩ ÆEIIIOYΩ is easily Эйоу, some god's name. Some wild spelling of Yehowah (but here, in that jehova we clearly see EOA, which reminds me of how it went in greek musical notation)

And if A was added later, if B was the Beginning, then EIOU is.. but it's not eihowah, but iehowah, so it's ioa or eoa (o is vav, thus its EVA, and E is the "the", thus it's VɅ. The opposite of OM (ɅV)?)

Nani being what in Japanese and where in Inupiaq may represent the semantic shift beween neighbours.

Аум продолжается в н превращаясь в Аминь, Ауминь.

Ау это и слово, кстати. Очень особенное. Descanding scale. AE of amen is anohter scale, ascending.

But then since nobody reads this texts, why do I write them?

MN labial before lingual. And the word is not just word.

What am I doing here? Just thinking of the stuff hoping some good pieces coming. But I have found so many pieces, maybe it's time to lay out the main picture of them?

The next seance:

After Bridge Comes Down (found in vol.25 and simnce forgotten, so how many good pieces are there)

it made me realize that the lines are different languages in which the same saying should be siad.

And Be Good Dog.

Be Good could be all there was (after bridge comes down is probably just one of first attempts to decypher it, and it fails falls down when you comapare it to Be Good. Even with A.

Be good deus?

Be ~ big (tiny are less there are, they're almost gone, almost none)

Such hypothesis may explain similarity of lines (languages are often similar) and sharing of k's and differences in the I-line. Whether I is India or Italia shall give us further clues.

Anglia: Be Good

España: ser bueno, estar bien

Estonia: ole hea

hEllenico: να είσαι καλά

Latin: bonum esse

Italian: essere buono, giovare

hIndi: अच्छा बनो [achchha bano (ача is good, bano is probably related to be)]

Acha Bano as indian Be Good, for that is A B. And weaving languages into such fabric I perform.

Ukrainian: Бути Добрим

Hungarian: légy jó (literally "fly good") and that led to it's own fucking story: g

but then, on another look, no, "legyen" is "to be" (it is both, the words are homonyms)

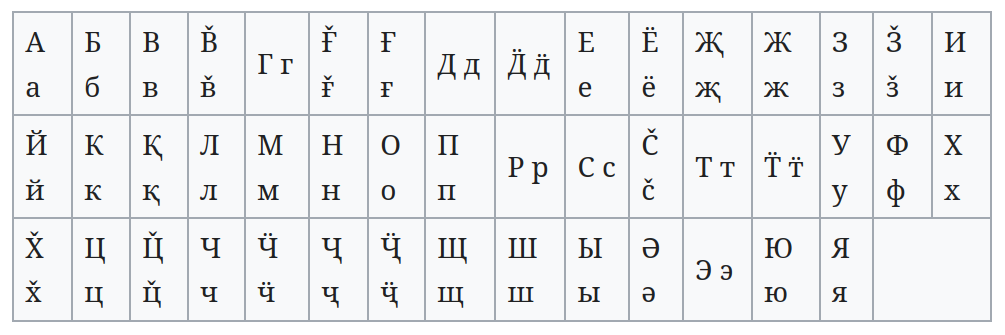

Hungarian alphabet is such a mess:

but if you cut the crap, it's basically A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

There are too many languages, even in Europe alone. I should leave that Be GooD ~ Jo Legi hypothesis for when I have some powerful language model doing the job.

A Á B C Cs D Dz Dzs

Ai Be G-D

Ai Be CoDe

Ai Be GooD

Ah Be G-D could it be? It is as something from the bible (somebody wrote those words alright)

Ah Be Gea

Et Вы θea (ik ben peter du bist paul rhyme influenced this line. I don't know what the line is, but this is a guess no worse than any other. Until a better comes along)

And here I can see how G and θ look very much alike

I aM

Is our world in turmoil because IMNL became ILMN (Immanuel became Ill man)

Is it IMNL or IMLN, because both are possible, and N is under H this way, and L is under Г, so let's explore the possibility of IMLN: I aM LuNa

Ah Baal?

Not now, Baal. Later. I aM LuNa is super awesome.

calculate

calendar

collect

call

calling дар? Names to the days it gives.

календы могут быть от него производным словом (a particular star in the sky is a term way more complicated than a wood with cuts of measure.

28 is natural number for how many days, and is it what allowed new letters to be added to some 7vowels making raws of four elements each.

e l m n could be the elemental, and then in the context of several lines ago, emelents? emenelts? emeralds? M R L as the sonor line? Middle, Right, Left? KMNL the communal?

Yin and Yang are Yinь and Yanъ, and as g ъ plays great, because upper half of it is г[g] and the belly is as of g. o = v!? г = v?! so far I dunno.

Alphabets appeared all at once. There are was period when it was secret. And probably the Greek Dark Ages taught humanity to.. they were secret during the Dark Ages. Scum probably went all oever wizards in CumBoJo/CumPuссia way.

M R L N as the line of sonors reminds one magical name: Merlin. Marilyn is even more so.

MRLN as the I-line? A I Y as the three the most different sounds of A I U, A I V, Ʌ I V

UYOI (wanted to say something, forgot what (and, as I mentioned before for I sentences, good))

yuio a weird set of vowels on qwertyuiop[]\ row

they're I and YOU. They're U&I surrounded by you

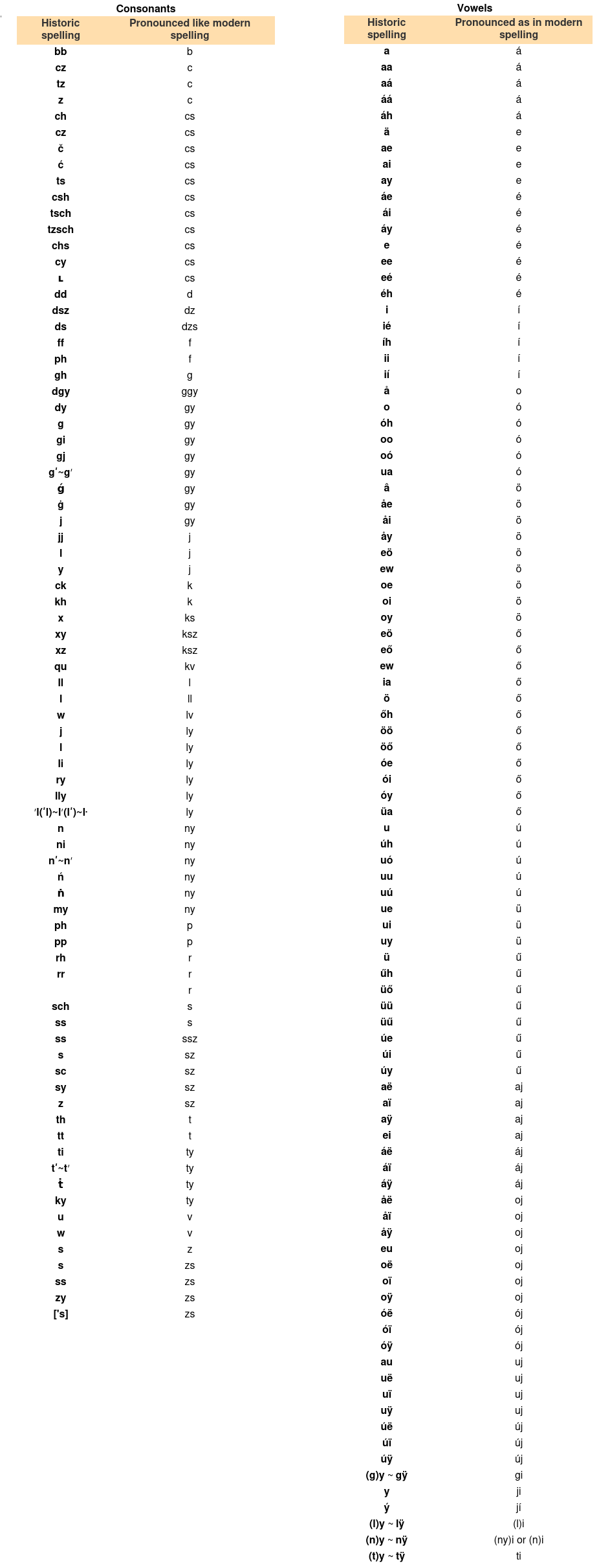

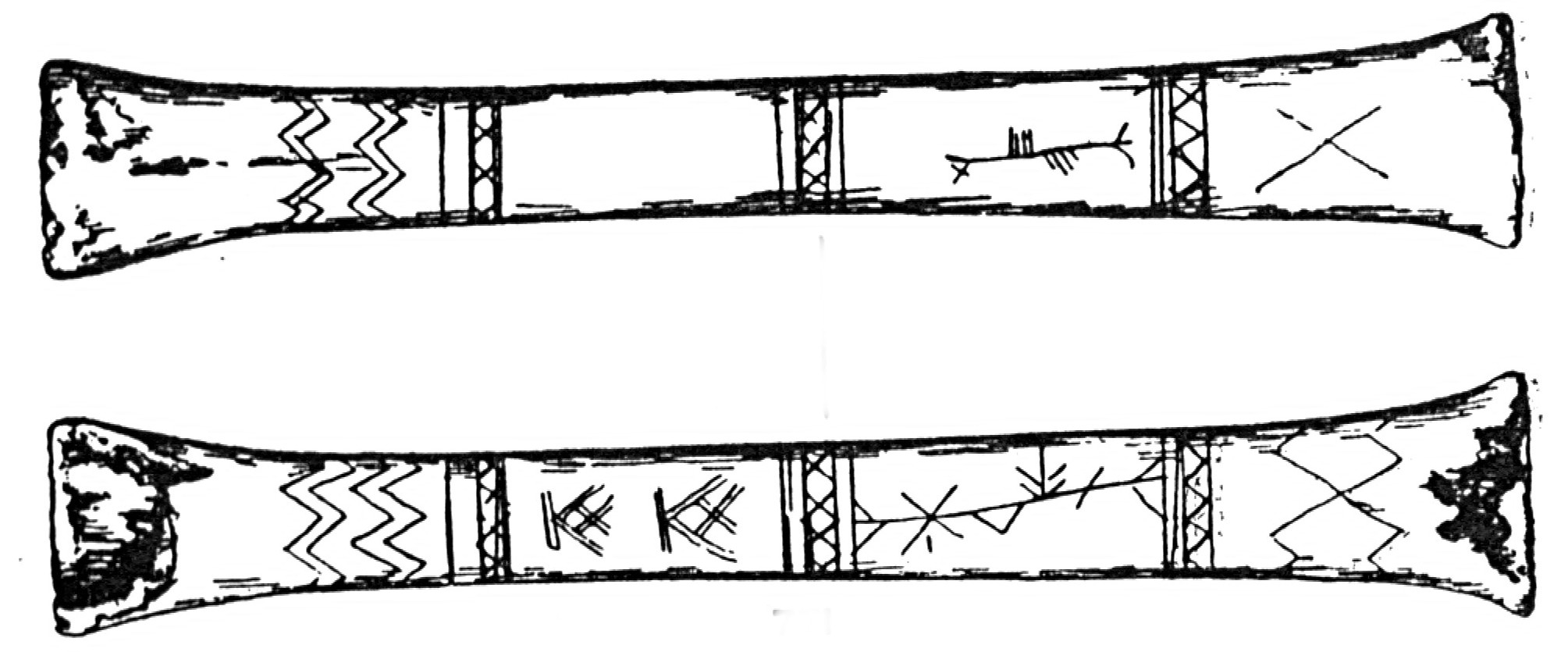

The Tullycommon bone has a short Ogham inscription next to various decorative elements such as zigzag lines on each side.

The characters are clearly Ogham characters.[3] A fact that is also typical of Ogham inscription lines with those used start and stemlines whose tips go through the main line. In order to mark the beginning of one of the two inscriptions, instead of the arrow running to the right, as with the Buckquoy spindle-whorl, an X next to the stemline is used.

The signs for C and S are clearly recognizable as Ogham signs on one side of the bone. On the other side may also be recognized the sign for the sound sequence EA (which was also used for K and resembled an X)[4] as well as the sign for M (character before stemline).

It is not possible to decipher the inscription. According to Macalister, "It makes no sense to decipher a short inscription of this kind ...".[5] If these are not doodles, the signs may actually have been used for magical purposes.[2] Perhaps the bone was one of a whole series of bones used for fortune-telling.[5]

They so easily say that it's "clearly Ogham", since two of those shapes are not ogham: one is ᚦ-like and the other is not known even in runes,

᚛ ᚁᚂᚃᚄᚅ ᚆᚇᚈᚉᚊ ᚋᚌᚍᚎᚏ ᚐᚑᚒᚓᚔ ᚕᚖᚗᚘᚙᚚ᚜

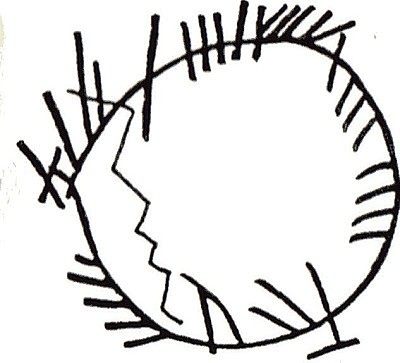

Buckquoy spindle-whorl they mentioned, and it is also rather interesting:

The Buckquoy spindle-whorl is an Ogham-inscribed spindle-whorl dating from the Early Middle Ages, probably the 8th century, which was found in 1970 in Buckquoy, Birsay, Orkney, Scotland.[1] Made of sandy limestone, it is about 36 mm in diameter and 10 mm thick.[2] It is the only known spindle-whorl with an Ogham inscription.

The inscription was once used as proof that the Pictish language was not Indo-European, being variously read as:

E(s/n)DDACTA(n/lv)IM(v/lb)

(e/)(s/n/)DDACTANIMV

(e/)TMIQAVSALL(e/q)[3]

However, in 1995 historian Katherine Forsyth reading

ENDDACTANIM(f/lb)

proposed that the inscription was a standard Old Irish ogham benedictory message, Benddact anim L. meaning "a blessing on the soul of L.".[4] The stone from which the whorl was made, and on which the inscription was written, is likely to have originated in Orkney.[5]

Let's try and see those transliterations in it. The Katherine's transliteration I start with:

ᚓ(e) ᚅ(n)

and I lost her

Here comes a more funny artefact:

(Sashahvi could be Саша хуй (Alex is dick))

"на балтике" ~ "на болотах"

is Hello cognate to Health (is H the V of Vale the way

ha is wa in japanese?) and are they cognates to Здарова

in the context of Здеся being Here? Are we looking at

some phonetic fluidity or a pareidolia phenomenon?in that sense [ḍa]𑀟~ᛋ[s]

𑀛 reminds both Ч and it's reading shows how much Ч reminds J and y

Ч is to J as q is to g IO (you know how they draw J sometimes, with that Ч-like top)

And truly brahmi reminds european alphabets more than paleo-hispanic does:

𑀕 ~ 𐤂

𑀔 ~ Г (just as with 𑀛~Ч, brahmi letters seem reversed.

𑀱 ~ ש

𑀴 ~ L (un-mirrorwed this time, which makes me wonder if that's not a later borrwoing from europe)

𑀓 for ka

𑀓𑀸 for kā that's so close in the way they use that ̄

𑀓𑀼 for ku reminds v opposing ʌ way too much

It's as if they were the first main letters, and u being low is very european (opposite to arabic, yet I said that) yet their i-syllables get higher than a: 𑀓𑀺 for i, 𑀓𑀻 for ī

𑀓𑁂 for ke sets it at the hight of ka, only the other way, different. and that e doesn't have a long variant makes it different from russian.

𑀓𑁄 for ko makes o the middle ground between e and a. how is it possible? with different vowels it may be, I need to hear how they read them first, vowels of different nations are different, so..

The way kØ reminds kā confuses me, probably they sound really symilar. But am I supposed to delve into languages I don't speak at all? How else am I supposed to learn it (I keep on forgetting that these are not books, they are my notebooks, I can do anything here)

The way 𑀮[la] reflects 𑀴[ḷa] makes it easy to remember them at once, but what are they?