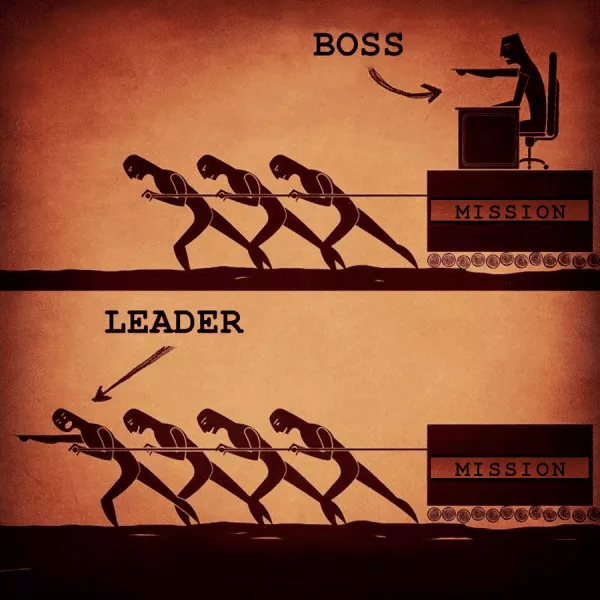

Here is a place to figure out the pronouns:

ya is you in english, but I in russian

the and they are righteously similar, but thee? thou? ты? - 3 лицо в одном случае, 2 в другом.

он is probably one. one is someone. some one. (found in vol.12 where I lead this chapter from)

ani is I in hebrew, but they in russian: они.

am and one? maybe, maybe not.

Λ

I

V

can be seen as

el, elle

I

Вы

but, also as

delal (he, no anonymity here)

delai (you, anonymity here)

delau (I, anonymity here)

This kind of anonymity between 1 and 2 persons reflects ya being you in english and I in russian.

I and V are both vowels, and both roman numerals too, btw. I is я, V is ю, and they go like эюя.

thus

Λ

I

V

are not suffixes, but pronouns:

eL, a, ᛆ, 1

I я

V is post-T syllable or glyph or whatever, and 2nd person is the most fresh, probably because of this grammatic invention we had to move from duality to trinity.

before we invented Вы, we used We. and thus и looking like u in cursive: и & u is explained.

It was all:

Λ

V

arrow outside and arrow inside to show world (and people) outside or the person inside.

A of e of ex

V of в of in

E-ва слово того периода? вынь-сунь? о, это сексуальо

ебать таким образом вынь-сунь-ть, to вынь-сунь.

wo (I (we)) in russian can be found in verbal suffix -u which indicates first person.

Then -i indicates second person, -ish indicates second person too, which is interesting, because not onl y I is first person in english, but also german ich is read as ish in bavaria. And that is another example of pronouns antonymy, especially because U is you in dutch, and in english u would be understood as you even though some modernist like joyce or welsh used y, which is related to u not only through greek Υ standing at the U's position, but also because russian у is u (and these phenomena are related, so no wonder, but that previous coincidence is wonderful indeed)

Suffix of the third person is -t (-et in singularis and -yut in pluralis, which is also yet to understand)

and it is pretty much universal: that is тот in russian, they can be translated as те.

Some antonymity is present in te and ты, using for the second person the same т(t) we use for 3rd one.

Tradition (он)

Традиция (я)

Does it tell that tradition is something russian? Rus is backwards, Bacward is the word. And see it's maeanings. Backward are traditional. With their ver vector being backwards.

отсталый, прошлое, в обратном направлении, задом наперёд (рачьё в детстве поёт песню про "кверху жопой" две старушки помошли, помолились и ушли кверху жопой. гугл говорит, что это ном, но я вроде слышал это ещё в прошлом веке. могу быть неправ)

traditio has that io at the end as well. Rome? Rome.

Those who even tradition are having on as in going on, they naturally culturally have a better basis for being the leaders.

ni is chinese you

ani is jewish I, as if a- is that un-, ã-, non- (as if their I is "not you" but then it was ambiguous because они is also "not you")

ны[ny, ~ni] could be old form of мы (we) because нас [nas] (us)

(greetings from vol.20)

Russian т is т when in cursive, and there's some unity between t & m:

тянИ ~ манИ

утянуть ~ умыкнуть ~ умять ~ уминать (тебе~мне? тепе[tepe] ~ mene?)

a very interesting dictionary I've found: http://hramiliya1787.ru/index.php?page=slovarik

Е — то, оное, его.

И — его, их.

Ю — её.

Я — их.

(я в значении "их" перекликается с ich в значении я)

вот ещё приколъ: Бе — он был, она была, оно было; бех — я была, был; бехом — мы были; бесте — вы были; беша, беху — они были.

(хотя этому место скорее в когнатах, подле английского be, но поскольку в русском таких словей никто давно не помнит, так что и для меня пока под вопросом справедливость этих словарей, пусть лежит всё вместе в этом странном месте)

И в значении он (в других словарях - ий, ый, узнаваемый как суффикс прилагательных сегодня)

greetings from vol.24

еврейский суффикс им скорей всего когната с русским местоимением им, потому что это местоимение множественного числа (а им в иврите это суффикс множественного числа) и третьего лица, впрочем это уже ..но впрочем тоже, очень подходящее местоимение, чтоб стать глагольным суффиксом. дать им = датим (даём? но в ём это м от мы. мы и им как антонимы! первое и третье лицо. И видимо он это носовое о, и это м of Oм

a lady testifies that japanese suffix ore (single male 1st person pronoun) used to be 2nd person pronoun:

and she also mentions that boku (more polite form of ore) is still used as 2nd person pronoun too.

and that jibun is used as both me and you (what a weird language, and how many more keys to solving the questions we may have it may bring!)

greetings from vol.27:

т = те:

сравни: сделаю сделают

развернуся развернутся

Во всех случаях т превращает глагол первого лица в глагол третьего лица.

Сделаю (её, ей, ɪo, iö)

Сделаем (им)

сделаё

сделаё̃

?

(где ё = я = io, a ё̃ = мы, we, nos)

сделаешь тогда что? а сделаете (literally те (they, but сделаете is used not with they, but with you)

сделай (jeNL)

сделаю (io)

тогда сделайте = сделай(jeNL)

сравни французский и нидерландский je (подобная история, что и в русском и английском ya)

ya & je похоже что когнаты, потому что ведут себя сходным образом (обе я и ты в соседних языках:

je в голландском ты, а во французском я.

ya в английском ты, а в русском я)

Занимательно, что русские в этом похожи на французские, а голландские на английские (географически подобное разделение makes perfect sense. и этнически тоже: голландский и английский германские (а к русском с фрацнузским присоединяется итальянский и его io))

в русских суффиксах эти когнаты встречаются: в сделай эта й you, в сделаю эта ю io.

сделаешь может быть "сделай же" "сделай уж" сделаjej (русский суффикс как свидетельство что jej читалось как jeʒ?!

в сделайте и сделают похоже что содержится то же самом те

сделают

сделает

ты ~ те? те множественное число от ты? те множественное число от та! и то, и тот. и ты?

sie is both she, you, they.. which may tell of the ancient unity between all pronouns other than the 1st.

w~m (wir, mir) as the opposite of d~s? (die, sie)

sie as you can be шь in russian сделаешь сдела jij sie?

和[わ(wa)] is the old name for Japan, which links it to the 🇯🇵.

And it's more than just old: Wa is the oldest recorded name of Japan.

and another wa, with no chinese character, just わ is me, I, which strongly resonates with personal pronouns originally being names of the nations.

ἡμεῖς (мы) иные формы: более современное εμείς [emís] и сокращение μεις [mis]

ὑμεῖς (вы) [imís]

звучат совершенно одинаково (т.е. омофоны)

что может свидетельствовать о изначальном единстве местоимений мы и вы и we

и может даже me

Собственно, me свидетельствует о том, что мы первично,

и что уже из него произошли индивидуалистское me и командно-коллективистское вы,

и, быть может, это непосредственно связано с социальным устройствоми российских го-в.

Т.е. чтоб переформатировать россию, следует заменить русский на английский.

И это о чём я сейчас столь скомканно и непослдовательно сказал? Что м~w.

we~me in english and мы~вы in russian.

Но вы~you as v~u

Gosh, it is complicated, on the right of hypothesis, but what kind of hypothesis is this?

we is collective, including speaker

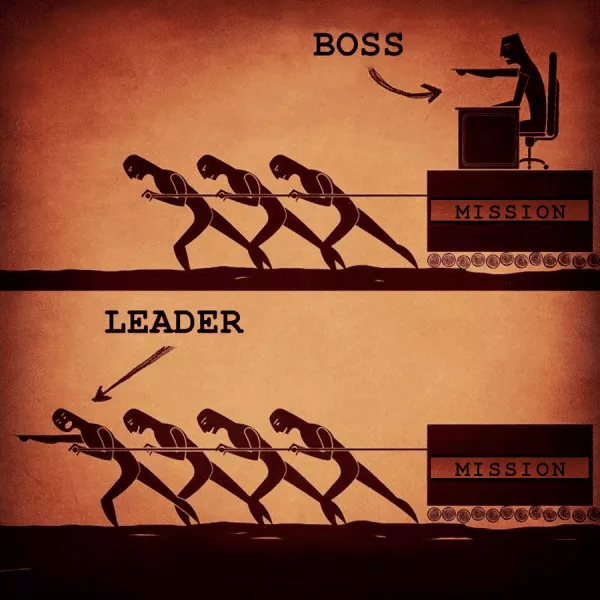

вы is командное, разница как между лидером и боссом

and somehow it divided in both languages, and once again me is more individualist, but мы is collectivist, but then we is collectivist, but in russian it is вы, which excludes personal responsibility at all.

Собственно, me свидетельствует о том, что мы первично,

и что уже из него произошли индивидуалистское me и командно-коллективистское вы,

и, быть может, это непосредственно связано с социальным устройствоми российских го-в.

Т.е. чтоб переформатировать россию, следует заменить русский на английский.

И это о чём я сейчас столь скомканно и непослдовательно сказал? Что м~w.

we~me in english and мы~вы in russian.

Но вы~you as v~u

Gosh, it is complicated, on the right of hypothesis, but what kind of hypothesis is this?

we is collective, including speaker

вы is командное, разница как между лидером и боссом

and somehow it divided in both languages, and once again me is more individualist, but мы is collectivist, but then we is collectivist, but in russian it is вы, which excludes personal responsibility at all.

onto-

from Ancient Greek ὤν (ṓn), present participle of εἰμί (eimí, “I am”).

Prefix

onto-

being

εἰμί as me and I am at the same time, and ὤν as он

Present participle is told to be form with ing in english (past participle is usually with ed, which indeed has sense of action in the past, even if the state is in the present: it's fucked tells that it was fucked (or fucked, or even fucked up) before that. We have the result of the actions in the past.

So that ὤν is az esmm)

But then what russian sophisticators call ontolinguistics, in english is called Developmental Linguistics

So prefix onto is actually about the way it came into being.

делай и делаю перевернули английские I & you: I delaio, You delay (well isn't I io, isn't Y yij)

she and he are different readings of ich reversed

wir could be reversed they (ð~z~ž~r; y~v~w (well, yea, I know, it's quite a pull))

vi is you in italian (and russian (rus is latin word, btw, romanians are we not?))

vi is we in norwegian (and english)

greetings from vol.45:

English and German don't seem to have such

homonyms.

Probably they were in more tight contact so they didn't allow the confusion.

Those pronouns alone show how Russians want to be with Brits, not Germans.

(english 1st person is 2nd person in russian; german 1st person is 3rd person in russian)

In english we and you are also phonetically inverted.

(in both cases the first vowel is shortened, so basically they're iu a nd ui

U is you in dutch.

I is me in english.

Did those two give birth to you and we? you is iu (тебе значит я вам (в тебе не я, а те?))

ui (мы значит вы мне? (мы вместе. we~me мы~мне, мы значит мне?))

если iu значит тебе (at least in sentences like "I give you")

если ui значит мне (вы мне. о благословенный русский!)

те в тебе не ты ле? не те ли? те вам? бе как вы? бе как старинная форма вам? была такая?

как we~мы так и you~им?

(блин, я запутался. интересная гипотеза, пускай ии сомкнёт)

похвалиΛRU ~ похвалиVUA

иΛ ~ il (he, which corresponds the meaning of that suffix)

иV ~ I've (at first I thought that it doesn'c correspond, but then that suffix can be used with the first person pronoun as well, all it stands for is the past tense for the verbs in male gender. So the "il" part is to the point, but so is "I've" (could it be that the neighbouring nations had the same words, but interpreted them differently?))

𒌋(ge₁₄) is not 1, but ten (and also [U (and imun and kiguru)], and in Elamite it's I[u]

э is english e borrowed into russian. Foreign e.

So are all couples like that? я=аз in the past (а was named аз in the past)

How comes we say я instead of а?

Was aз ~ a the antonymy of pronouns? was russian first person аз seen as third person in english an?

кому-то мы, а кому-то 'em (them is probably the 'em, the М (but what am I talking about, me is pan-european. me and 'em could be the opposition))

Аз is Us the way Me is Мы

(is = is a cognate of)

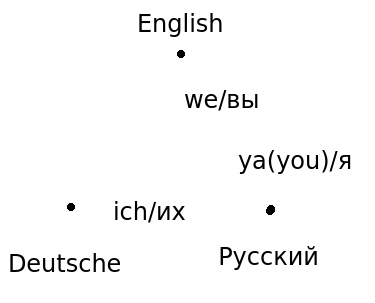

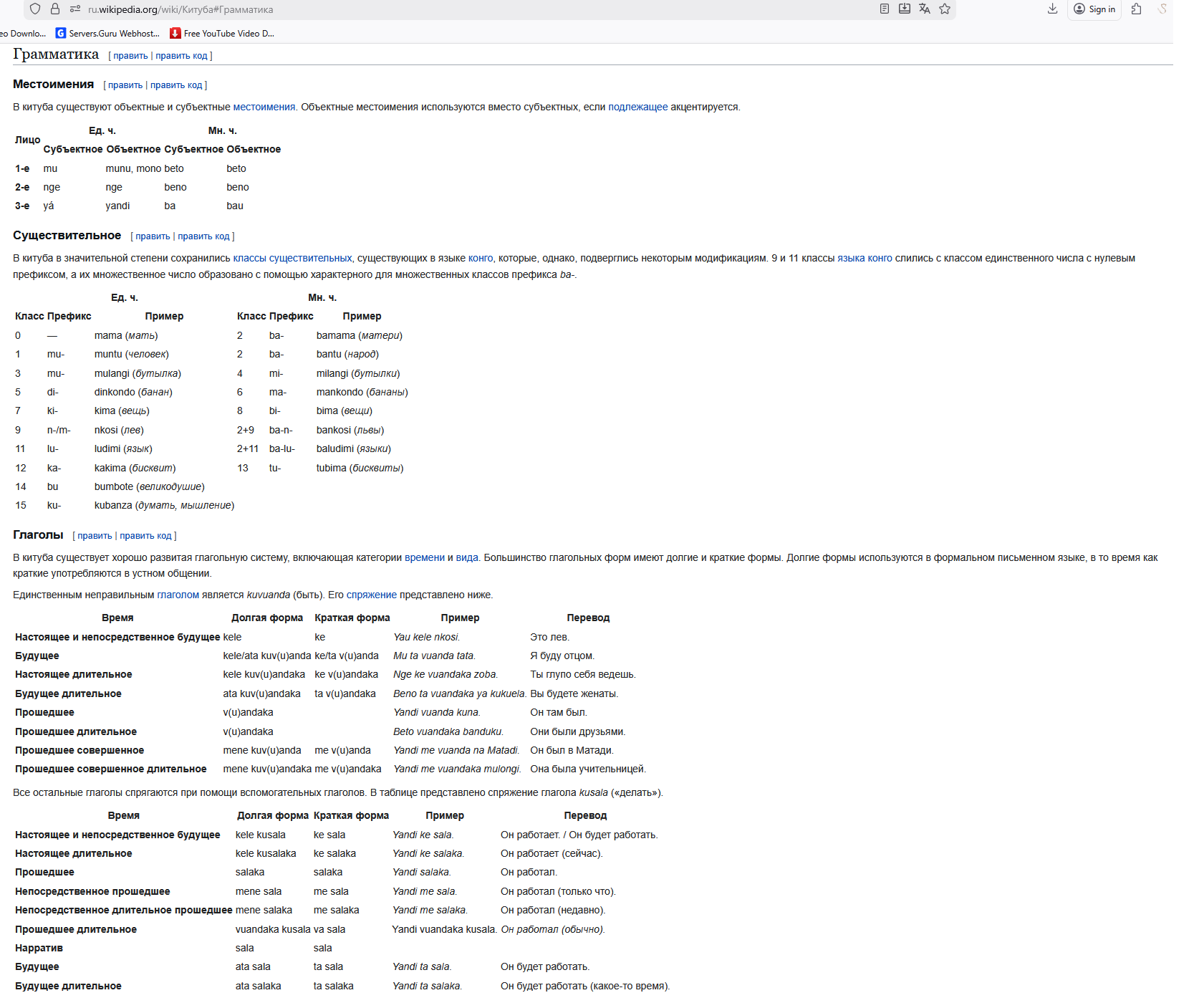

я is он в африке:

но мама и мню универсальны. Мы пили из одного источника? Мы пили из одной груди?

((мне)мене) mini ~ тіпі (типи (тиби (тебе)))

Probably they were in more tight contact so they didn't allow the confusion.

Those pronouns alone show how Russians want to be with Brits, not Germans.

(english 1st person is 2nd person in russian; german 1st person is 3rd person in russian)

In english we and you are also phonetically inverted.

(in both cases the first vowel is shortened, so basically they're iu a nd ui

U is you in dutch.

I is me in english.

Did those two give birth to you and we? you is iu (тебе значит я вам (в тебе не я, а те?))

ui (мы значит вы мне? (мы вместе. we~me мы~мне, мы значит мне?))

если iu значит тебе (at least in sentences like "I give you")

если ui значит мне (вы мне. о благословенный русский!)

те в тебе не ты ле? не те ли? те вам? бе как вы? бе как старинная форма вам? была такая?

как we~мы так и you~им?

(блин, я запутался. интересная гипотеза, пускай ии сомкнёт)

похвалиΛRU ~ похвалиVUA

иΛ ~ il (he, which corresponds the meaning of that suffix)

иV ~ I've (at first I thought that it doesn'c correspond, but then that suffix can be used with the first person pronoun as well, all it stands for is the past tense for the verbs in male gender. So the "il" part is to the point, but so is "I've" (could it be that the neighbouring nations had the same words, but interpreted them differently?))

𒌋(ge₁₄) is not 1, but ten (and also [U (and imun and kiguru)], and in Elamite it's I[u]

э is english e borrowed into russian. Foreign e.

So are all couples like that? я=аз in the past (а was named аз in the past)

How comes we say я instead of а?

Was aз ~ a the antonymy of pronouns? was russian first person аз seen as third person in english an?

кому-то мы, а кому-то 'em (them is probably the 'em, the М (but what am I talking about, me is pan-european. me and 'em could be the opposition))

Аз is Us the way Me is Мы

(is = is a cognate of)

(from vol.49)

ссыпается ет = это

ссыпайся й = you (ю (italian io) u v вы)

ссыпаюсь ю = io = я

ссыпаясь? было это формой первого лица?

ссыпався было формой второго числа? Вы Второго Те Третьего Я? Яко́го

ссыпаемся ем = мы

ссыпаешься ешь = ты (а ел = il (is el of est?))

ссыпаются ют = они? эти? какие-то дикие древние напрочь устаревшие местоимения?

am = мы?

am = we? could wordies be reversed and remain themselves? Were rune just rune, was upside rune a demand to work on that element, to focus on it in both cases. What were rune laying sideways? Maybe they were rectangular and maybe the seer the seeer layed out runes it wanted to tell of? Maybe they could read them by the fingertips and lay out the runes which are to be spoken of. It's an art of speech.

нас нам

us am

I am = Я нам? Mijn naam. I am~named

us&am as Ϻ&M?

ссыпается ет = это

ссыпайся й = you (ю (italian io) u v вы)

ссыпаюсь ю = io = я

ссыпаясь? было это формой первого лица?

ссыпався было формой второго числа? Вы Второго Те Третьего Я? Яко́го

ссыпаемся ем = мы

ссыпаешься ешь = ты (а ел = il (is el of est?))

ссыпаются ют = они? эти? какие-то дикие древние напрочь устаревшие местоимения?

am = мы?

am = we? could wordies be reversed and remain themselves? Were rune just rune, was upside rune a demand to work on that element, to focus on it in both cases. What were rune laying sideways? Maybe they were rectangular and maybe the seer the seeer layed out runes it wanted to tell of? Maybe they could read them by the fingertips and lay out the runes which are to be spoken of. It's an art of speech.

нас нам

us am

I am = Я нам? Mijn naam. I am~named

us&am as Ϻ&M?

я is он в африке:

но мама и мню универсальны. Мы пили из одного источника? Мы пили из одной груди?

((мне)мене) mini ~ тіпі (типи (тиби (тебе)))

.

.